Classroom Management: A Persistent Challenge for Pre-Service Foreign Language Teachers

Manejo del salón de clase: un reto persistente para docentes practicantes de lenguas extranjeras

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.43641Keywords:

Classroom management, foreign language, pre-service teachers, teacher education (en)Docentes practicantes, educación docente, lengua extranjera, manejo de clase (es)

This qualitative descriptive study aimed to ascertain the extent to which classroom management constituted a problem among pre-service foreign language teachers in a teacher education program at a public university in Colombia. The study also sought to identify classroom management challenges, the approaches to confronting them, and the alternatives for improving pre-service teachers’ classroom management skills. The results revealed that classroom management is a serious problem with challenges ranging from inadequate classroom conditions to explicit acts of misbehavior. Establishing rules and reinforcing consequences for misbehavior were the main approaches to classroom management, although more contact with actual classrooms and learning from experienced others were alternatives for improving classroom management skills.

Este estudio cualitativo descriptivo buscó determinar en qué medida el manejo de clase constituye un problema para docentes practicantes de lenguas extranjeras en un programa de licenciatura en inglés en una universidad pública Colombiana. El estudio buscó identificar los desafíos de manejo de clase, el enfoque para afrontarlos, y las alternativas para mejorarlos. Los resultados revelaron que el manejo de clase es un problema serio que va desde condiciones inadecuadas del salón hasta actos explícitos de indisciplina. Establecer reglas y consecuencias por indisciplina fueron el principal enfoque de manejo de clase mientras que mayor contacto con sitios de práctica y aprender de otros con experiencia fueron alternativas de mejoramiento.

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.43641

Classroom Management: A Persistent Challenge for Pre-Service Foreign Language Teachers

Manejo del salón de clase: un reto persistente para docentes practicantes de lenguas extranjeras

Diego Fernando Macías*

Universidad Surcolombiana, Neiva, Colombia

Jesús Ariel Sánchez**

EE Miller Elementary, Fayetteville, USA

*diego.macias@usco.edu.co

**jesussanchez@ccs.k12.nc.us

This article was received on May 23, 2014, and accepted on January 9, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Macías, D. F., & Sánchez, J. A. (2015). Classroom management: A persistent challenge for pre-service foreign language teachers. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 17(2), 81-99. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.43641.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This qualitative descriptive study aimed to ascertain the extent to which classroom management constituted a problem among pre-service foreign language teachers in a teacher education program at a public university in Colombia. The study also sought to identify classroom management challenges, the approaches to confronting them, and the alternatives for improving pre-service teachers’ classroom management skills. The results revealed that classroom management is a serious problem with challenges ranging from inadequate classroom conditions to explicit acts of misbehavior. Establishing rules and reinforcing consequences for misbehavior were the main approaches to classroom management, although more contact with actual classrooms and learning from experienced others were alternatives for improving classroom management skills.

Key words: Classroom management, foreign language, pre-service teachers, teacher education.

Este estudio cualitativo descriptivo buscó determinar en qué medida el manejo de clase constituye un problema para docentes practicantes de lenguas extranjeras en un programa de licenciatura en inglés en una universidad pública Colombiana. El estudio buscó identificar los desafíos de manejo de clase, el enfoque para afrontarlos, y las alternativas para mejorarlos. Los resultados revelaron que el manejo de clase es un problema serio que va desde condiciones inadecuadas del salón hasta actos explícitos de indisciplina. Establecer reglas y consecuencias por indisciplina fueron el principal enfoque de manejo de clase mientras que mayor contacto con sitios de práctica y aprender de otros con experiencia fueron alternativas de mejoramiento.

Palabras clave: docentes practicantes, educación docente, lengua extranjera, manejo de clase.

Introduction

The student teaching practicum, which constitutes the first time many students in teacher education programs actually teach in real classrooms, is considered an “opportunity [for pre-service teachers] to apply theoretical knowledge and skills, previously gained in the [teacher education] classroom, to authentic educational settings” (Williams, 2009, p. 68). However, this practicum generates various challenges that pre-service teachers will face. Issues such as overcrowded classrooms, students at different levels of language proficiency (Sariçoban, 2010), “classroom discipline, assessing students’ works, the organization of class work, relationships with parents, and insufficient and/or inadequate teaching materials” (Veenman, 1984, p. 143) often plague teachers when they first enter the teaching profession.

Soares (2007) claims that teacher educators overlook the issue of classroom management by putting forward theories and pedagogy that revolve around the concept of ideal learners. This leaves pre-service teachers with a sense of hopelessness and with “little but their intuition to guide them” (Soares, 2007, p. 43) in coping with disruptive situations and incidents in their classrooms. Although “teacher education programs cannot hope to account for all the different types of settings and conditions beginning teachers will inevitably encounter” (Farrell, 2006, p. 212), it is their responsibility to guide pre-service teachers into discovering alternatives and implementing strategies to deal with issues inherent to the teaching profession, including classroom management. This guidance eases their transition from teacher preparation programs to real classroom settings and thus increases their likelihood of success.

We administered a questionnaire and interviewed pre-service teachers, practicum supervisors, and cooperating teachers in an English teacher education program to determine if classroom management constituted a problem and to identify classroom management challenges, the approaches used to confront them, and the alternatives for improving classroom management skills. Although this is not the first study to address the issue of classroom management in Colombia or elsewhere, it served to diagnose the problem of classroom management in this teacher education program.

Review of the Literature

The Teaching Practicum

The teaching practicum has been defined as “the major opportunity for the student teacher to acquire the practical skills and knowledge needed to function as an effective language teacher” (Richards & Crookes, 1988, p. 9). A practicum experience can be classified as direct or indirect. In a direct experience, student teachers adopt a supervised or unsupervised teaching position in a real classroom, whereas in indirect experiences, they watch someone else teach the class (Cruickshank & Armaline, 1986). The participants in this study were engaged in a direct supervised teaching experience.

According to Richards and Crookes (1988):

The practice teaching typically begins with observation of the cooperating teacher, with the student [teacher] gradually taking over responsibility for teaching part of a lesson, under the supervision of the cooperating teacher. Supervision may take the form of occasional or regular visits by the supervisor, reports to the supervisor from the cooperating teacher or the student, peer feedback, or conferences with the supervisor. (p. 20)

In relation to the support provided by schools and colleagues, Farrell (2003) showed that “the transition from the teacher training institution to the secondary school classroom is characterized by a type of reality shock in which the ideals that were formed during teacher training are replaced by the reality of school life” (p. 95). In learning to face this reality, pre-service teachers must face and address many types of issues and challenges including classroom management.

Classroom Management: Definition and Causes

Classroom management has been defined as the “actions taken to create and maintain a learning environment conducive to successful instruction” (Brophy, 1996, p. 5). It is also thought to consist of integrating four areas: “establishing and reinforcing rules and procedures, carrying out disciplinary actions, maintaining effective teacher and student relationships, and maintaining an appropriate mental set for management” (Marzano, 2003, p. 88). It follows that classroom management should not be seen as synonymous with classroom discipline; it involves those other aspects mentioned above that are equally inherent to teaching. Crookes (2003) similarly sees a well-managed classroom as a relatively orderly room in which “whatever superficial manifestations of disorder that may occur either do not prevent instruction and learning, or actually support them” (p. 144). What the above definitions of classroom management have in common is establishing an appropriate environment and therefore order in the classroom so that teaching and subsequently learning can take place.

Classroom management has been regarded as a serious challenge for many pre-service and even in-service teachers (Balli, 2009; Quintero Corzo & Ramírez Contreras, 2011). The challenge stems from many possible issues involved in managing a classroom. Brown (2007) affirms that classroom management involves decisions about what to do when:

- You or your students digress and throw off the plan for the day.

- An unexpected but pertinent question comes up.

- Some technicality prevents you from doing an activity.

- A student is disruptive in class.

- You are asked a question to which you do not know the answer.

- There is not enough time at the end of a class to finish an activity that has already started.

In regards to the impact of classroom management on the teaching practicum, Stoughton (2007) revealed that classroom management was identified by pre-service teachers “as a subject about which there is a fairly wide disparity between what is taught in university classes and seminars and the theoretical construct upon which many behavioral plans are based” (p. 1026). Equally important are the specific problems pre-service teachers find during their practicum. These may include disruptive talking, persistent inaudible responses, sleeping in class, unwillingness to speak in the target language (Wadden & McGovern, 1991), “insolence to the teacher, insulting or bullying other students, damaging school property, refusing to accept sanctions or punishment” (Harmer, 2007, p. 126) and lack of interest in class (Soares, 2007).

Even though classroom management is an area of interest and preoccupation for pre-service language teachers, it has not been extensively researched in Colombia. Chaves Varón (2008), in looking at the strengths and weaknesses in a teaching practicum, found that student teachers were not being properly trained to manage a classroom, and Insuasty and Zambrano Castillo (2011) identified classroom management as one of the most commonly discussed issues during the feedback sessions between supervisors and pre-service teachers.

Castellanos (2002) found that factors such as the environment and teachers’ attitudes were among the causes of children’s aggressive behavior when playing competitive games in the English classroom. This study highlighted students’ self-esteem and teachers’ fair treatment in class as elements that might help teachers to maintain positive atmospheres in their classrooms. Prada Castañeda and Zuleta Garzón (2005) also identified some of the difficulties (e.g., giving instructions, introducing the topic, managing the classroom) that four primary school pre-service teachers had in their practicum and the strategies they used to deal with them (e.g., reflecting on their own experiences and knowledge, setting objectives for immediate action, and examining whether or not their actions had been successful).

In a more recent study, Quintero Corzo and Ramírez Contreras (2011) sought to help teacher-trainees overcome indiscipline in the English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom. They found heterogeneous classes, lack of academic interest, affective factors, parental neglect, and education policies as reasons for indiscipline in EFL classes. Some of the strategies participants claimed to be effective in coping with discipline problems were:

- Making instructions clear and giving them before grouping students.

- Keeping learners busy, always giving them something to do within the allotted time.

- Managing time wisely.

- Preparing and including attractive materials.

- Stating rules for class procedures and activities, emphasizing the consequences for breaking the rules.

- Giving the students responsibilities.

- Changing activities frequently.

- Monitoring students by walking around the classroom.

- Respecting differences among learners, considering their backgrounds and learning paces and styles. (Quintero Corzo & Ramírez Contreras, 2011, p. 68)

These studies have helped to consolidate a rather scarce but growing body of research in the area of classroom management in English language teaching in Colombia. This phenomenon has become a prominent challenge for many pre-service teachers who are about to enter the teaching profession. These teachers constantly struggle to implement strategies to reduce the negative impact of poor classroom management in their practicum.

Classroom Management Models and Approaches

A number of approaches have been proposed to help teachers address classroom management in their lessons. Wolfgang and Glickman (1986) talked about three categories for problem solving in classroom practice: relationship/listening, rules/rewards, and confronting/contracting. The first stresses the need for a facilitating environment in which the teacher supports students’ inner struggles to solve problems in class. The second focuses on the teacher’s taking control of the environment, and rewards, rules, and punishment are used to ensure students’ appropriate learning behavior. The third emphasizes the teacher’s constant interaction with the students, both working together to arrive at joint solutions to problems of misbehavior; students are encouraged “to take responsibility for their actions but need the active involvement of a kind but firm teacher” (Wolfgang & Glickman, 1986, p. 19).

Other models for classroom management include the assertive discipline model (Canter & Canter, 1976), which suggests that at the beginning of the year, teachers must establish a discipline plan that includes rules and procedures and consistently apply consequences for misbehavior, and the withitness and overlapping model (Kounin, 1970), which focuses on teachers constantly scanning the whole classroom to assess if students are paying attention or doing what they are supposed to, also known as “eyes in the back of his head” (Kounin, 1970, p. 81). This model also highlights overlapping, or what the teacher does when he has two or more matters to address at the same time. Another model is the choice theory model (Glasser, 1990), which sees teachers as leaders and attempts to rid them of the thought that if students are not punished, they do not learn. Teachers are urged to help students make good decisions and to remind them that they are capable of performing and behaving well in class. This model also encourages teachers to conduct class meetings whenever they deem it necessary so that students can evaluate themselves and design plans for improvement.

Weber (as cited in Pellegrino, 2010) similarly talks about three authority types: traditional, which involves students’ following the teacher’s management based on cultural learned behaviors; legal/rational, through which the teacher establishes his authority after creating and reinforcing a set of values and rules whereby “obedience is not owed to the individual, but rather the impersonal order instead”; and charismatic authority, which “relies on personal devotion to the figure that possesses the qualities exalted by the followers” (Weber as cited in Pellegrino, 2010, p. 64).

Such models and approaches helped us to characterize the issue of classroom management in the present study and to answer the research question related to how pre-service teachers currently deal with classroom management issues in the practicum. Although it is not our goal here to fully advocate a particular approach to managing the classroom, we are more inclined to consider views such as Wolfgang and Glickman’s (1986) confronting-contracting perspective, Glasser’s (1990) choice theory model, and Weber’s legal/rational authority based on rational values and established rules. Nonetheless, we must highlight that no classroom management style or approach should be fully adopted or constructed without taking into serious consideration the characteristics of the teaching setting. The present study may help teachers to determine which approach or model best fits the needs of their particular contexts.

Method

This study followed a qualitative descriptive orientation in that it involved interacting with people in their social contexts and talking with them about their perceptions (Glesne, 2011) regarding classroom management. Accordingly, the study considered participants’ views initially gathered through a questionnaire and then further explored them via semi-structured interviews. The study was conducted in the context of an undergraduate EFL teacher education program at a public university in Colombia. Students enrolled in this program had to take 147 credits to be certified as EFL teachers. The program curriculum was organized into three large formation fields: Discipline Specific, Teacher Professional Identity, and Socio-Cultural Identity & Development (Trans.). The first of these sought to help students develop their communicative competence in English, and the third aimed at developing students’ socio-humanistic competencies. However, it was the second field—Teacher Professional Identity—that focused directly on the areas of pedagogy and didactics. These areas involved courses such as general pedagogy, methods, and the teaching practicum.

Within the field of Teacher Professional Identity, students had to complete two practicum periods, which were meant to give them the possibility of gaining experience by teaching English for one academic semester at a primary school and another one at a secondary school, both usually located in the same city where the teacher education program was offered. As stated in the course objectives of the teaching practicum syllabus, this teaching experience “gets pre-service teachers involved with aspects such as lesson planning, teaching skills, students’ assessment, extra-curricular activities, use of resources, and reflection and self-evaluation” (Universidad Surcolombiana, 2004, p. 2, [Trans.]).

Pre-service teachers are placed in a school in mutual agreement with the practicum coordinator. Cooperating teachers are then chosen according to the courses available at each school and whether or not they accept to work with a pre-service teacher throughout the semester. Finally, practicum supervisors are appointed by the practicum coordinator based on their availability and workload regulations established by the university. Typically, practicum supervisors must observe pre-service teachers and meet with them at the university to give them feedback on lesson plans and observations at least once a week.

The questions that guided this study were as follows:

- To what extent is classroom management perceived as a problem for pre-service teachers in their practicum?

- What classroom management challenges do pre-service teachers typically encounter in their practicum?

- What characterizes the approach pre-service teachers use to deal with classroom management issues in their practicum?

- What are participants’ views of possible alternatives for improving pre-service teachers’ classroom management skills throughout their EFL teacher education program curriculum?

Participants

The study involved the participation of 34 pre-service teachers, 10 practicum supervisors, and 17 cooperating teachers in the EFL teacher education program. There were 20 female and 14 male pre-service teachers. Seventeen were in public primary schools and 17 in public secondary schools. Similarly, 18 of the 34 pre-service teachers were in their first practicum period, with the remaining 16 in their second period, which means that the latter group had one semester of accumulated teaching experience as pre-service teachers. Cooperating teachers (13 female, 4 male) and practicum supervisors (6 female, 4 male) were selected based on their extensive experience hosting and supervising pre-service teachers, 6-7 years for the former and 10 years average for the latter both in primary and secondary schools.

Participants were initially approached in person as a group in one of the practicum meetings at which they accepted participation in the study of their own free will by signing a consent letter. Following the ethical procedures, they were then asked to respond to an initial online questionnaire (Appendix A). Afterward, a smaller sample of 10 pre-service teachers, six practicum supervisors, and six cooperating teachers from among those who had agreed to be part of the study was invited for follow-up semi-structured interviews (Appendix B). Each interview was arranged in consultation with those participants who had stated in the questionnaire that classroom management constituted a problem in the practicum and who had agreed to take part in a follow-up interview. Codes1 were used throughout the study to guarantee the principles of anonymity and confidentiality.

Data Collection and Analysis

The use of these methods and types of participants contributed to validating the data and achieving triangulation. We piloted the questionnaire with colleagues and some former students of the same teacher education program. The purpose of the questionnaire was to collect participants’ demographic information and to gain their initial insights on the research questions. The follow-up semi-structured interview sought to obtain a more in-depth view of the answers provided in the questionnaire and to elicit potential stories or additional insights regarding classroom management.

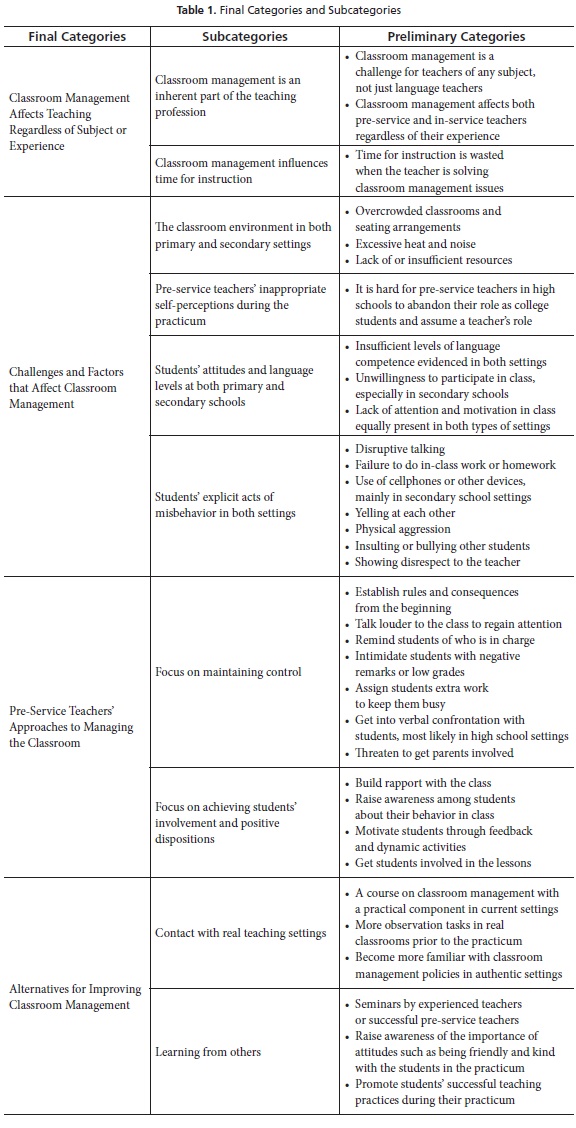

We used grounded theory as the approach to analyze the data. Corbin and Strauss (1990) observe that this technique enables researchers to conceptualize the social patterns and structures of the information through a constant process of comparison. Grounded theory is a systematic process that involves three main stages as follows: Open coding involves using colors to code the different patterns that emerge as a result of comparing the data. In this study, these codes were directly connected to the research questions. After a rigorous process of comparison, we named every phenomenon and copied and pasted all of the related statements in a separate document to define the initial preliminary categories. Axial coding occurs within one category, making connections between subgroups of that category and creating connections between one subcategory and another. Here, we found relationships between the subcategories, and we then designed a chart (Table 1) containing four main categories and the associated subcategories. These categories were broken down into specific issues that helped explain the general findings of the study. This chart was permanently improved as more data emerged and as a result of the constant process of comparison. Selective coding similarly involves validating relationships and refining and developing the final categories (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Categories are integrated, and a grounded theory emerges. In this final stage, we were able to integrate all categories into the final four broad categories, which helped us to present the findings in a more orderly fashion.

Findings

The following categories illustrate the main findings of the study:

Classroom Management Affects Teaching Regardless of Subject or Experience

Some of the participants, particularly cooperating teachers in high schools, claimed that the classroom management issues pre-service teachers encountered in the practicum were inevitably part of the teaching profession and not exclusive to language teaching. They were aware that it was something pre-service teachers had to confront and learn along the way regardless of the subject they had to teach. For example, CT3 made the following claim:

Now I realize that many student teachers have to suffer because of the indiscipline of the students, but it is not only with EFL student teachers, it is with all the teachers, with the math teacher, the P.E. teacher, the religion teacher, with all of them...students misbehave.

Further evidence of classroom management being a problem was observed when pre-service teachers in secondary school claimed that classroom management interfered with instructional time. They stated that they often had to stop the lesson to solve all kinds of situations in class:

All the time one spends managing the discipline...organizing things...the class does not last one hour but forty minutes and what can one do in forty minutes?...time flies and one can do nothing. (PT4)

Similarly, PT18, while doing his practicum at a high school, felt that it was difficult to use the teaching methods and strategies he had been taught in the teacher education program because he had to devote so much time to organizing the students before he could start the lesson:

At times, all that [we learned in the teacher education program] about the communicative methodology...is complicated to manage...because one has to concentrate on getting the students to settle down, to be seated, to listen to the instructions, and then the last ten minutes is the time we have for class.

This can be connected to Farrell’s (2003) observation that the ideals that pre-service teachers receive during their preparation programs are replaced by the hard reality of school life. This may have led participants to perceive mismatches between what they had learned in their teacher preparation and what they encountered in real school classrooms.

Challenges and Factors That Affect Classroom Management

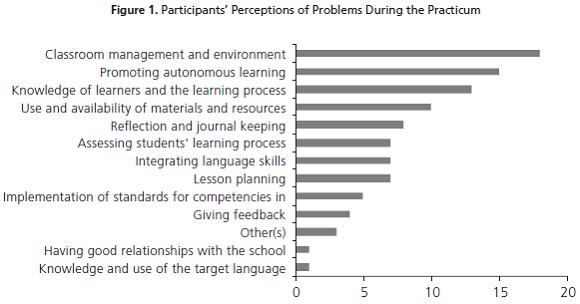

Managing the classroom during the practicum was initially reported as a serious problem on the online questionnaire by participants in both primary (62%) and secondary (47%) school settings, and the follow-up interviews provided more robust evidence of the same tendency. Figure 1 shows a condensed view of the problems identified by participants in both settings.

In regards to specific classroom management challenges that pre-service teachers encountered in their practicum, many such challenges had to do with external, nonacademic factors that influenced students’ behavior or did not contribute to an adequate learning atmosphere in the context of primary and secondary schools. One such factor was the high temperatures in class because the weather in the city was usually very hot and the classrooms were not equipped with air conditioning or ceiling fans. Noise from outside was another factor that was usually caused by different sources (people on the street, students in other classrooms, cultural and social activities inside the school, etc.). In addition, other factors included overcrowded classrooms, inconvenient seating arrangements, and lack of or insufficient resources. The comments below illustrate some of those problems:

These are relatively large groups of 40 students with whom one has to deal, with many problems such as noise, indiscipline, the changing moods of students. (PT6)

Sometimes the classroom was hot; there were ceiling fans but some of them just did not work. There was no air conditioning...and the room was large and there were windows, but anyways the heat was always felt...Students said that it was very hot. (PT12)

Another factor that made classroom management difficult, especially for pre-service teachers at high schools, was that they could not see themselves as teachers in the practicum: “at the beginning one does not see oneself as a teacher but as a college student that is carrying out an activity” (PT2). They felt that this had serious implications because the high school students did not see them as their teachers either, and they were more inclined to challenge their authority and be disrespectful toward them. Therefore, they felt they needed to be firm and assertive so that their students would take them more seriously. PT4 made the following remark:

I had a lot of problems to gain the respect I deserved, to be seen as a teacher...because they addressed me as “viejo” (old man), or they talked to me as if I were one of them. Then gaining their respect has been really difficult, as well as getting them to follow the instructions I give them.

This may inevitably lead pre-service teachers to feel uncommitted and discouraged from doing the job or developing a passion for the teaching profession. As claimed by Pellegrino (2010), “novice teachers, who are viewed by most students as temporary and not supreme authority in the classroom, have a more difficult time establishing traditional authority in the classroom” (p. 3).

Some other issues were related to students’ language levels and attitudes toward the class. These issues included students who had difficulties understanding or expressing their ideas in English, unwillingness to participate, and lack of attention and motivation in class. This lack of interest and motivation, according to practicum supervisors at primary and high schools, was sometimes accompanied by feelings of boredom and frustration, which then led to students being disruptive and caused other classroom management issues.

To further illustrate the issue of lack of interest and attention in class, PT10 commented on an incident he had with one of his students. The pre-service teacher contacted the student’s parents because the child was not showing any progress or interest in class. The child’s mother then came to the school and said that her son was having conflicts with another boy who was bothering him. The pre-service teacher said that he was not aware of that incident and that he was still concerned about the child’s lack of progress in class. In the end, the child’s mother blamed the pre-service teacher for not paying enough attention to what was going on in class. This incident equally served to illustrate the relationships with parents, noted by Veenman (1984), as another factor that pre-service teachers have to face during the practicum.

Linked to the previous factors, there were other issues ranging from minor acts of misconduct (e.g., disruptive talking, tardiness, failure to do homework) to major acts of misbehavior such as yelling at each other, physical aggression, and insulting or bullying other students. For instance, CT5 told us about an episode a pre-service teacher at a secondary school had in one of his colleague’s lessons:

One day she [the pre-service teacher] had a group of students who got into a fight in class and then as the incident was getting out of control, she requested the cooperating teacher’s assistance. However, there was such chaos that the academic coordinator had to go to the classroom to try to settle everyone down. Soon after, a police officer was called in, after a few moments...in the middle of the chaos...the students got hold of the police officer’s gun. The officer noticed the gun was missing when he was outside the classroom. The gun was immediately recovered from the top of a desk. Later the students stated that they had taken the gun just for fun.

This may have been an isolated incident, but it certainly had a huge impact on the pre-service teacher in that it let her experience the complex reality of classrooms, especially in terms of the potential dangers of situations like this one. When the incident occurred, the pre-service teacher reported that she was shocked but also somewhat relieved because she had seen how the cooperating teacher and the academic coordinator had also not been able to manage the situation. As a former practicum supervisor, one of the researchers had pre-service teachers come to the feedback sessions with great discomfort and frustration because of the extreme situations they faced at their practicum sites.

Pre-Service Teachers’ Approaches to Managing the Classroom

Regarding the approaches that pre-service teachers used to manage their classrooms, responses varied depending on the nature of the problem or situation. However, focusing on maintaining control appeared to be the most predominant approach among pre-service teachers across school settings. Most of the participants, including cooperating teachers and supervisors, claimed that pre-service teachers made great efforts to control students’ behavior in class by establishing and reinforcing strict rules from the beginning and reminding students of the harsh consequences if they did not follow the rules. This approach typically involved talking louder to the students to regain their attention, writing notes in their notebooks so that their parents could see them, reminding students of who was in charge, intimidating students with negative remarks or low grades, assigning extra work in class just to keep them busy, and at times getting into verbal confrontations with students. In this respect, PT26 affirmed that students’ lack of discipline was very common in class and so, at times, he had to raise his voice, talk louder to the students, and be tough with them so that they would pay attention. PT1 made use of similar strategies:

Sometimes I regain their attention by talking loudly and angrily. I change their seats. Sometimes I see myself confronting them, and then I bring the students’ records folder [with the intention of writing a negative remark].

The strategies used by these pre-service teachers tended to reflect an authoritarian approach to managing the class, which has common characteristics with the assertive discipline model (Canter & Canter, 1976) and the traditional authority type (Weber as cited in Pellegrino, 2010). Another tendency, mainly among pre-service teachers at secondary schools, was to seek the assistance of the cooperating teacher or to refer students directly to the discipline coordinator or principal whenever they misbehaved in class. This was perceived by a small number of practicum supervisors as strong dependence on others and may have contributed to reaffirming the view that pre-service teachers did not see themselves as teachers who were capable of managing situations on their own.

To a much lesser extent, three of the pre-service teachers at primary schools and one at a secondary school favored a more friendly approach to managing the classroom. They privileged actions such as building rapport, raising awareness among students about their behavior in class, motivating students through positive feedback and dynamic activities, and involving students in the lessons. Some of these actions can be associated with the categories of relationship-listening and confronting-contracting (Wolfgang & Glickman, 1986) to problem solving characterized by the teacher’s being supportive while working collaboratively with the students to build a positive learning environment. In this respect, PT21 made the following remark:

I talked to the student alone and then tried to make him reflect on what happened in class. I asked him what makes him feel uncomfortable, why he gets into so much disruptive talking, why he misbehaves in class.

One of the cooperating teachers similarly added:

Student teachers try to bring them many games because this is what cooperating teachers do not do; they do not play with the students...then some student teachers try to be more active, more dynamic (CT14)

These pre-service teachers used an approach based on gaining students’ confidence and respect. This way of managing conflicts and disruptive actions may have a strong connection with the personality type of each pre-service teacher. Based on our personal experience with pre-service teachers in the same teacher education program, some of them were usually calm and patient and therefore appeared to be more effective at managing the classroom. Similarly, as was claimed by one of the practicum supervisors, these pre-service teachers may have adopted this style as a result of “having accumulated experience from their first practicum period mostly in high school” (PS2). Additionally, two of them had acted as substitute English teachers for short periods of time at two private schools in the city.

Alternatives for Improving Classroom Management

In terms of alternatives that the EFL teacher education program could implement to help pre-service teachers improve their classroom management skills, participants in both types of settings emphasized that the program should offer them more opportunities to be involved in authentic school settings. Most pre-service teachers and some cooperating teachers claimed that this could be achieved through different strategies, such as a course on classroom management with both theoretical and practical components, more specific observation tasks prior to the beginning of the practicum, more supervision and feedback during the practicum, and spending more time in current school contexts so that they could get acquainted with classroom management policies. Specifically, PT22 commented:

I think that we need a bit more reality. It is too much theory, and sometimes one gets to the classroom and one has forgotten everything. It would be something that prepares us better so that one gets there and feels ready, like I know what to do, I know what I can find there, I know what things may go well and what things may go wrong. It has to be something that brings us closer to the reality of the schools.

PT26 similarly affirmed:

The micro-teaching sessions of the methods courses should take place in the real context...in a classroom with 40 students and not just for one or two classes but for two months or a month...so that at the time of the practicum when we get a group of students to teach...we have had a previous warm-up to get to this.

Participants also highlighted the relevance of learning from experienced in-service or successful pre-service teachers, which could be in the form of seminars, debates, or talks. For instance, PT7, PT4, and PS9 felt that there should be workshops and talks with practicum supervisors and pre-service teachers where they could share their both positive and negative experiences in classroom management. These workshops, added PS9, may also serve to highlight pre-service teachers’ attitudes such as being friendly and kind with the students during the practicum and familiarize them with the school context, especially in terms of guidelines or regulations for effective classroom management.

Conclusions

Participants in this study indicated that classroom management is a serious problem for most pre-service teachers in their practicum across primary and secondary school settings. Similarly, the phenomenon of classroom management appears to be inherent to the teaching profession, and it affects instructional time. The classroom management challenges pre-service teachers usually encounter, regardless of the school setting, range from inadequate conditions in the classroom environment, pre-service teachers’ seeing themselves as college students as opposed to teachers, and learners’ negative attitudes and low language levels to more explicit acts of misbehavior such as physical aggression, insulting or bullying other students, and showing disrespect to the teacher.

It was also evidenced that pre-service teachers’ dominant approach to managing the classroom centered on maintaining control through establishing rules and reinforcing consequences for negative behavior; only a few focused on seeking student involvement and cultivating students’ positive dispositions toward the class. Additionally, more and earlier contact with real teaching settings and opportunities to learn from other successful or more experienced others were identified as the main alternatives for improving classroom management skills.

Participants equally suggested alternatives that include a course on classroom management, which has never been offered by this teacher education program; more observation tasks, which have been limited to two or three hours before the practicum starts; and promoting and socializing successful teaching practices with new pre-service teachers throughout the practicum.

Recommendations

Future curriculum revisions and research initiatives in this teacher education program should contribute to integrating the practical and theoretical input (Yan & He, 2010) and to strengthening the existing school-university partnerships in preparing language teachers. Such partnerships can help to reduce the gap between pre-service teachers’ experiences as provided by teacher education programs and the real school settings where they have to conduct their practicum. Similarly, these curriculum revisions should respond to participants’ suggestions such as learning from experienced others and more and earlier involvement with real school contexts.

Further analysis of the classroom management approaches participants appeared to favor in this study constitutes another avenue of inquiry. It would be interesting to generate opportunities for pre-service teachers to characterize and reflect on their own approaches to managing the classroom and so encourage them to explore other approaches (e.g., Glassner, 1990) by which the teacher becomes a leader manager as opposed to a boss manager or by which students can assume responsibility for their own behavior and take a more active role in building a more effective learning atmosphere.

Limitations of the Study

If we were to perform this study again, we would use classroom observation as another method to collect data because it would give us more explicit evidence of the problem and would help us validate the perspectives obtained through the questionnaires and the interviews. It would also be relevant to seek the involvement of school students so that their views as other key players in the practicum experience can either reaffirm or challenge those provided by pre-service teachers, practicum supervisors, and cooperating teachers.

1PT1 = Pre-service teacher 1, CT1 = Cooperating teacher 1, PS1 = Practicum supervisor 1.

References

Balli, S. J. (2009). Making a difference in the classroom: Strategies that connect with students. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Brophy, J. (1996). Teaching problem students. New York, NY: Guilford.

Brown, H. D. (2007). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. White Plains, NY: Pearson Longman.

Canter, L., & Canter, M. (1976). Assertive discipline: A take-charge approach for today’s educators. Seal Beach, CA: Canter & Associates.

Castellanos, A. (2002). Management of children’s aggressiveness when playing competitive games in the English class. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 3(1), 72-77.

Chaves Varón, O. (2008). Formación pedagógica: La práctica docente en la Licenciatura en Lenguas Modernas de la Universidad del Valle [Teacher education: The practicum at the Modern Languages Licenciatura of Universidad del Valle]. Lenguaje, 36(1), 199-240.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Crookes, G. (2003). A practicum in TESOL: Professional development through teaching practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Cruickshank, D. R., & Armaline, W. D. (1986). Field experiences in teacher education: Considerations and recommendations. Journal of Teacher Education, 37(3), 34-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718603700307.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2003). Learning to teach English language during the first year: Personal influences and challenges. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(1), 95-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00088-4.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2006). The first year of language teaching: Imposing order. System, 34(2), 211-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2005.12.001.

Fowler, J., & Şarapli, O. (2010). Classroom management: What ELT students expect. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 3, 94-97.

Glasser, W. (1990). The quality school: Managing students without coercion. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Oxford, UK: Pearson Education.

Insuasty, E. A., & Zambrano Castillo, L. C. (2011). Caracterización de los procesos de retroalimentación en la práctica docente [Characterizing the feedback processes in the teaching practicum]. Entornos, 24, 73-85.

Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Marzano, R. J. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Pellegrino, A. M. (2010). Pre-service teachers and classroom authority. American Secondary Education, 38(3), 62-78.

Prada Castañeda, L., & Zuleta Garzón, X. (2005). Tasting teaching flavors: A group of student teachers’ experiences in their practicum. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6(1), 157-170.

Quintero Corzo, J., & Ramírez Contreras, O. (2011). Understanding and facing discipline-related challenges in the English as a foreign language classroom at public schools. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 59-72.

Richards, J. C., & Crookes, G. (1988). The practicum in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 22(1), 9-27. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587059.

Sariçoban, A. (2010). Problems encountered by student-teachers during their practicum studies. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 707-711.

Soares, D. (2007). Discipline problems in the EFL class: Is there a cure? PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 8(1), 41-58.

Stoughton, E. H. (2007). “How will I get them to behave?”: Pre service teachers reflect on classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(7), 1024-1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.001.

Universidad Surcolombiana. (2004). Microdiseño curricular de práctica docente [Curricular micro-design for the teaching practice]. Neiva, CO: Author.

Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 54(2), 143-178. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543054002143.

Wadden, P., & McGovern, S. (1991). The quandary of negative class participation: Coming to terms with misbehavior in the language classroom. ELT Journal, 45(2), 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/45.2.119.

Williams, J. (2009). Beyond the practicum experience. ELT Journal, 63(1), 68-77. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn012.

Wolfgang, C. H., & Glickman, C. (1986). Solving discipline problems: Strategies for classroom teachers. Newton, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Yan, C., & He, C. (2010). Transforming the existing model of teaching practicum: A study of Chinese EFL student teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Education for Teaching, 36(1), 57-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607470903462065.

About the Authors

Diego Fernando Macías works as an assistant professor of English at the English Teacher Education Program at Universidad Surcolombiana. He is a Fulbright scholar who is currently pursuing his PhD in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching at the University of Arizona, USA. His interests include language teacher education and learning technologies.

Jesús Ariel Sánchez is a teacher from EE Miller Elementary in North Carolina, USA. He holds an MA in English Language Teaching from Universidad de la Sabana (Colombia) and an In-service Certificate in English Language Teaching from the University of Cambridge, UK. His research interests include classroom management and photography as a language learning tool.

Note: The interview and questionnaire formats presented here were used with pre-service teachers. Those for supervisors and cooperating teachers followed the same pattern but were worded accordingly.

Aim: To obtain participants’ views on the issue of classroom management in the practicum of an EFL teacher education program.

Directions: This questionnaire contains a series of items regarding your practicum experience. Please read and respond each question accordingly. OPEN QUESTIONS MAY BE ANSWERED IN ENGLISH OR SPANISH.

- Gender: Male ___ Female ___

- Period of teaching practicum: 1st period _____ 2nd period _____

- Current teaching practicum: Primary Education ___ Secondary Education ___

- Select from the aspects below those you consider to represent great difficulties in your teaching practicum:

- Lesson planning

- Implementation of basic standards for competencies in EFL

- Knowledge and use of the target language

- Integrating language skills

- Knowledge of learners and the learning process

- Classroom management and environment

- Assessing students’ learning processes

- Use and availability of materials and resources

- Reflection and journal keeping

- Giving feedback

- Promoting autonomous learning

- Having good relationships with the school community

- Other(s)? Please specify:

- Which of the following do you perceive as problems in your practicum lessons?

- Overcrowded classrooms

- Students at different levels of language proficiency

- Sitting arrangements

- Noise

- Heat

- Lighting

- Social and cultural activities

- Insufficient and/or inadequate teaching materials

- Time and length of the lesson

- Students’ lack of interest and motivation in class

- Disruptive talking

- Inaudible responses

- Sleeping in class

- Tardiness and poor attendance

- Failure to do in-class work

- Failure to do homework

- Cheating on tests

- Unwillingness to speak in the target language

- Insolence to the teacher

- Insulting or bullying other students

- Damaging school property

- Refusing to accept sanctions or punishment

- Use of cellphones or electronic devices

- Other(s)? Please specify:

- What do you typically do when any of the situations or actions in Question 5 above occurs in any

of your classes?

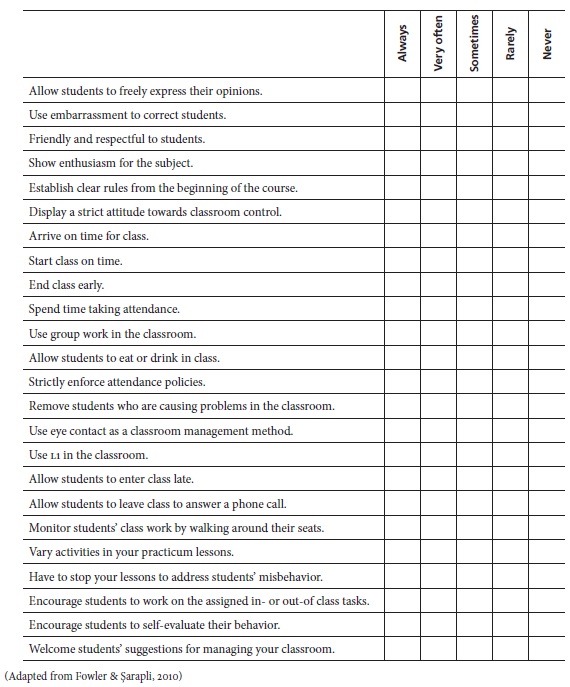

- How often do you... OR are you... in your practicum lessons?

- What alternatives should the EFL teacher education program offer student-teachers to help them improve their classroom management skills?

- What have been the most difficult factors you have had to address in your teaching practicum?

- In terms of classroom management, what would you say are the most common difficulties you usually confront in your practicum?

- Can you tell me about a time in your practicum when you had a problem with classroom management? What happened? What did you do?

- What strategies do you use to handle the classroom management issues in your teaching practicum?

- Did the EFL teacher education program curriculum provide you with enough orientation in strategies for managing problems related to classroom management before you started your practicum?

- What strategies should the EFL teacher education program implement to help pre-service teachers improve their classroom management skills?

- Is there any other comment or idea that you would like to add?

References

Balli, S. J. (2009). Making a difference in the classroom: Strategies that connect with students. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Brophy, J. (1996). Teaching problem students. New York, NY: Guilford.

Brown, H. D. (2007). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. White Plains, NY: Pearson Longman.

Canter, L., & Canter, M. (1976). Assertive discipline: A take-charge approach for today’s educators. Seal Beach, CA: Canter & Associates.

Castellanos, A. (2002). Management of children’s aggressiveness when playing competitive games in the English class. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 3(1), 72-77.

Chaves Varón, O. (2008). Formación pedagógica: La práctica docente en la Licenciatura en Lenguas Modernas de la Universidad del Valle [Teacher education: The practicum at the Modern Languages Licenciatura of Universidad del Valle]. Lenguaje, 36(1), 199-240.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Crookes, G. (2003). A practicum in TESOL: Professional development through teaching practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Cruickshank, D. R., & Armaline, W. D. (1986). Field experiences in teacher education: Considerations and recommendations. Journal of Teacher Education, 37(3), 34-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718603700307

Farrell, T. S. C. (2003). Learning to teach English language during the first year: Personal influences and challenges. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(1), 95-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00088-4

Farrell, T. S. C. (2006). The first year of language teaching: Imposing order. System, 34(2), 211-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2005.12.001

Fowler, J., & Şarapli, O. (2010). Classroom management: What ELT students expect. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 3, 94-97.

Glasser, W. (1990). The quality school: Managing students without coercion. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Oxford, UK: Pearson Education.

Insuasty, E. A., & Zambrano Castillo, L. C. (2011). Caracterización de los procesos de retroalimentación en la práctica docente [Characterizing the feedback processes in the teaching practicum]. Entornos, 24, 73-85.

Kounin, J. S. (1970). Discipline and group management in classrooms. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Marzano, R. J. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Pellegrino, A. M. (2010). Pre-service teachers and classroom authority. American Secondary Education, 38(3), 62-78.

Prada Castañeda, L., & Zuleta Garzón, X. (2005). Tasting teaching flavors: A group of student teachers’ experiences in their practicum. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 6(1), 157-170.

Quintero Corzo, J., & Ramírez Contreras, O. (2011). Understanding and facing discipline-related challenges in the English as a foreign language classroom at public schools. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 59-72.

Richards, J. C., & Crookes, G. (1988). The practicum in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 22(1), 9-27. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587059

Sariçoban, A. (2010). Problems encountered by student-teachers during their practicum studies. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 707-711.

Soares, D. (2007). Discipline problems in the EFL class: Is there a cure? PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 8(1), 41-58.

Stoughton, E. H. (2007). “How will I get them to behave?”: Pre service teachers reflect on classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(7), 1024-1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.001

Universidad Surcolombiana. (2004). Microdiseño curricular de práctica docente [Curricular micro-design for the teaching practice]. Neiva, CO: Author.

Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 54(2), 143-178. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543054002143

Wadden, P., & McGovern, S. (1991). The quandary of negative class participation: Coming to terms with misbehavior in the language classroom. ELT Journal, 45(2), 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/45.2.119

Williams, J. (2009). Beyond the practicum experience. ELT Journal, 63(1), 68-77. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn012

Wolfgang, C. H., & Glickman, C. (1986). Solving discipline problems: Strategies for classroom teachers. Newton, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Yan, C., & He, C. (2010). Transforming the existing model of teaching practicum: A study of Chinese EFL student teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Education for Teaching, 36(1), 57-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607470903462065

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

CrossRef Cited-by

1. Mohd Kaziman Ab Wahab, Hafizhah Zulkifli, Khadijah Abdul Razak. (2022). Impact of Philosophy for Children and Its Challenges: A Systematic Review. Children, 9(11), p.1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111671.

2. Narciso Castillo-Sanguino, María del Socorro Ramírez, Sandrine Kachiri Castillo-Lucero. (2024). Pedagogies of Compassion and Care in Education. Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design. , p.273. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-3613-7.ch012.

3. Büşra ÇAYLAN ERGENE, Mine IŞIKSAL. (2022). A Case Study on Pre-service Teachers’ Question Types within the Context of Teaching Practice Course. Muğla Sıtkı Koçman Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 9(1), p.1. https://doi.org/10.21666/muefd.887481.

4. Joan Kang Shin, Woomee Kim. (2021). Perceived impact of short‐term professional development for foreign language teachers of adults: A case study. Foreign Language Annals, 54(2), p.365. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12521.

5. Diego Fernando Macías. (2018). Classroom Management in Foreign Language Education: An Exploratory Review. Profile: Issues in Teachers´ Professional Development, 20(1), p.153. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n1.60001.

6. Di Zhu, Jing Chi, Jing Xu, Licheng Shen. (2022). Classroom management in CFL education at all-girls secondary schools in the UAE. Cogent Education, 9(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.2002132.

7. Marco Antonio Villalta Paucar, Sergio Martinic Valencia. (2020). Intercambios comunicativos y práctica pedagógica en el aula de los docentes en formación. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 22, p.1. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2020.22.e21.2513.

8. Martha García Chamorro, Monica Rolong Gamboa, Nayibe Rosado Mendinueta. (2022). Initial Language Teacher Education: Components Identified in Research. Journal of Language and Education, 8(1), p.231. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2022.12466.

9. John De Nobile, Mandy Yeates. (2025). Pre-service teacher concerns about inappropriate student behaviour: An Australian study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 166, p.105197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.105197.

10. Tania Tagle, Claudio Díaz, Paulo Etchegaray, Richard Vargas, Héctor González. (2020). CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT PRACTICES REPORTED BY CHILEAN PRE-SERVICE AND NOVICE IN-SERVICE TEACHERS OF ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE (EFL). Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 8(4), p.335. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.8434.

11. Xuerong Wang, Si Chen, Shuang Xie, Haihong Shi, Lu Zhang, Lifang Yang, Xiangyu Zhao, Lieny Jeon. (2026). Pre-Service Early Childhood Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy, Emotion Regulation Strategies, and Responsiveness to Children’s Emotions: A Latent Profile Approach. Early Education and Development, 37(1), p.148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2025.2548029.

12. Randa Abbas, Vered Vaknin-Nusbaum, Ari Neuman, Geraldine Mongillo, Dorothy Feola, Rochelle Goldberg Kaplan. (2018). The use of modern standard and spoken Arabic in mathematics lessons: the case of a diglossic language / El uso del árabe estándar moderno y del árabe hablado en las clases de matemáticas: el caso de una lengua diglósica. Cultura y Educación, 30(4), p.730. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2018.1519920.

13. Marianna Levrints. (2022). Overview of English language teaching challenges. The Journal of V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University. Series: Foreign Philology. Methods of Foreign Language Teaching, (95), p.99. https://doi.org/10.26565/2786-5312-2022-95-13.

14. Edgar Lucero, Ángela María Gamboa-González, Lady Viviana Cuervo-Alzate. (2024). The Conception of Student-Teachers and the Pedagogical Practicum in the Colombian ELT Field. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 26(1), p.169. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v26n1.105139.

15. Diego Fernando Macías, Carlos Alcides Muñoz, Jhon Jairo Losada-Rivas. (2025). Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions of Peer Support Groups for Enhancing Classroom Management Skills. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 27(2), p.173. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v27n2.114061.

Dimensions

PlumX

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2015 PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.