Building ESP Content-Based Materials to Promote Strategic Reading

Diseño de materiales basados en contenidos para fomentar estrategias de lectura en un curso de inglés con propósitos específicos

Keywords:

CALLA, learning strategies, materials development, reading (en)Diseño de materiales, estrategias de aprendizaje, lectura (es)

This article reports on an action research project that proposes to improve the reading comprehension and vocabulary of undergraduate students of English for Specific Purposes–explosives majors, at a police training institute in Colombia. I used the qualitative research method to explore and reflect upon the teaching-learning processes during implementation. Being the teacher of an English for specific purposes course without the appropriate didactic resources, I designed six reading comprehension workshops based on the cognitive language learning approach not only to improve students’ reading skills but also their autonomy through the use of learning strategies. The data were collected from field notes, artifacts, progress reviews, surveys, and photographs.

Este artículo informa sobre un proyecto de investigación cualitativa que propone mejorar la comprensión de lectura y el vocabulario de estudiantes universitarios de inglés que se especializan en temas relativos a explosivos en una escuela de policía, en Colombia. Por tratarse de un curso de inglés específico que carece de los recursos didácticos apropiados, diseñé seis talleres de comprensión de lectura basados en el enfoque del aprendizaje cognitivo de la lengua, para mejorar tanto su comprensión de lectura como su autonomía para usar estrategias de aprendizaje. Para la recolección de datos se emplearon notas de campo, artefactos, pruebas de progreso, encuestas y fotografías.

Building ESP

Content-Based Materials to Promote Strategic Reading

Diseño de materiales basados en contenidos para fomentar estrategias de lectura en un curso de inglés con propósitos específicos

Myriam Judith Bautista Barón

Universidad Externado de Colombia

bautistamyriam@yahoo.es

This article

was received on March 6, 2012, and accepted on November 20, 2012.

This article

reports on an action research project that proposes to improve the reading

comprehension and vocabulary of undergraduate students of English for Specific

Purposes–explosives majors, at a police training institute in Colombia. I

used the qualitative research method to explore and reflect upon the

teaching-learning processes during implementation. Being the teacher of an English for specific purposes course without the

appropriate didactic resources, I designed six reading comprehension workshops

based on the cognitive language learning approach not only to improve

students’ reading skills but also their autonomy through the use of

learning strategies. The data were collected from field notes, artifacts,

progress reviews, surveys, and photographs.

Key words: CALLA, learning strategies, materials development, reading.

Este

artículo informa sobre un proyecto de investigación cualitativa

que propone mejorar la comprensión de lectura y el vocabulario de

estudiantes universitarios de inglés que se especializan en temas

relativos a explosivos en una escuela de policía, en Colombia. Por

tratarse de un curso de inglés específico que carece de los

recursos didácticos apropiados, diseñé seis talleres de

comprensión de lectura basados en el enfoque del aprendizaje cognitivo

de la lengua, para mejorar tanto su comprensión de lectura como su

autonomía para usar estrategias de aprendizaje. Para la

recolección de datos se emplearon notas de campo, artefactos, pruebas de

progreso, encuestas y fotografías.

Palabras clave: CALLA, diseño de materiales, estrategias de aprendizaje, lectura.

Introduction

The students at the

Escuela de Investigación Criminal—a police training institute in

Bogotá—study English for specific purposes and there is an immediate

need to design didactic resources for teaching the classes effectively because

there are no appropriate materials related to crime in Colombia in English.

Besides, nowadays the abundance of English information found in journals,

articles, books, and web sites demands a good level of reading abilities. For

this reason, these students need to be competent in the comprehension of English

texts to promote their own practice and interest in their lives as police

officers.

Considering the

English for Specific Purposes (ESP) institutional goals and the students’

needs, I feel the main aim of this study was to understand whether and how

reading comprehension and strategy awareness can be developed through the

implementation of content-based materials anchored in the Cognitive Academic

Language Learning Approach (CALLA).

I developed and

implemented criminalistics materials to promote reading comprehension based on

CALLA by designing six reading workshops as didactic units that provide both

language and content learning activities, with an explicit focus on language

learning strategies, the inclusion of relevant content, the possibility for

interactive teaching and learning, and opportunities for students’

self-assessment of their own learning process. The workshops also allow me to

track the participants’ progress for interpretation and analysis of data

when necessary.

This situation aroused

my interest in materials development, so that I could provide my students with

authentic readings to help them achieve the pre-established learning

objectives. As a teacher, I consider that this student-centered approach helps

us to get closer to the students’ language needs and enhances the success

of our work. This research can motivate other teachers to develop

contextualized ESP materials as a regular pedagogical task, and I believe that

this study is a worthy example of how teachers can give the practice of

teaching a well-deserved boost in the education field.

Theoretical Framework

The pillars that

shape this research are reading comprehension, materials development and the

Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach. They were combined to set up a

productive work environment to fulfill the expectations of a group of police

officer trainees who were interested in learning about criminalistics as a

science that deals with processing criminal events. According to The California

Association of Criminalistics (CAC, 2010, p. 1), “This science involves

the application of principles, techniques and methods of the physical sciences

and has as its primary objective a determination of physical facts which may be

significant in legal cases.”

This was the main

curriculum subject at this school, so the students needed to be taught

vocabulary related to physical descriptions, clothes, belongings and evidence

elements relevant in a criminal investigation. Also, they needed to be familiar

with crime information and to read material dealing with criminal cases,

updated technologies in data analysis, fingerprints, explosives and weapons.

Reading Comprehension

The reading process

is not easy to examine be-cause it is complex and personal. Many communicative

events take place during the reading process and the reader has to cope with

them trying to comprehend and obtain as much as he/she can from the text. There

is a close relationship between the reader and the text (Alderson &

Bachman, 2000), and the reader’s perception of the material is affected

by life experiences and purposes.

Reading is a

complex, strategic, and active process of constructing meaning, not simply a

matter of skill application (Palinscar & Brown, 1984). Comprehension

requires a dynamic participation of the readers and their ability to seek,

organize and reformulate the information in their own words, resorting to their

own experiences and background knowledge.

To prepare students

to read, it is essential to overcome comprehension difficulties and prepare

them to be autonomous in the future. There are lots of effective ways to guide

them, but, unfortunately, sometimes teachers ignore them and tell students to

simply read and hope they become skillful in getting information without

planning any strategic steps i.e. organizing ideas, taking notes, using

reference skills, etc. In this respect, there are many kinds of effective

instructional activities that can help students comprehend and remember what

they read and as teachers it is our responsibility to make them available to

the students.

Additionally, the

reading process includes a variety of strategies, skills and types of texts

that make the reading task multifaceted and a combination of mental processes,

knowledge, and abilities. Grabe (2004, p. 55) suggests that “it should be

centered on the use of and training in multiple strategies to achieve

comprehension.” Then, the real value and effectiveness of the reading

process involve frequent practice with clear purposes and expectations.

Likewise, the use

of authentic and adapted readings helps students familiarize themselves with

specific content-based expressions and vocabulary, and become skillful at

consciously recognizing the organization of the information and the structure

of the target language. Students should also be trained in the use of

terminology related to their field of study, thus feeling more engaged (Scott

& Winograd, 2001).

Noles and Dole

(2004) state:

Researchers have collected much evidence that supports explicit strategy instruction. The teaching of strategies empowers readers, particularly those who struggle, by giving them the tools they need to construct meaning from text. Instead of blaming comprehension problems on students’ own innate abilities, for which they see no solution, explicit strategy instruction teaches students to take control of their own learning and comprehension. (p. 179)

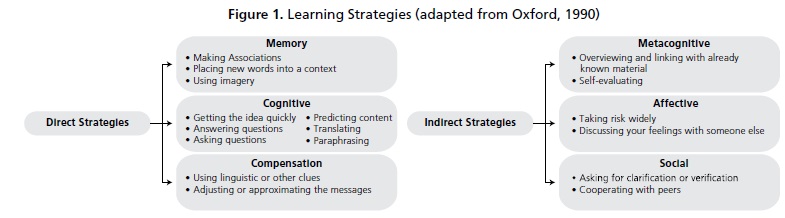

There is a variety

of direct and indirect learning strategies to facilitate reading comprehension

in the language learning process. From Oxford’s strategy classification

system (Oxford, 1990) I focused on direct strategies that allow the straight

learning and practice of content and vocabulary and indirect ones that help the

students organize and evaluate their knowledge and performance (see Figure 1).

Materials Development

Teacher-developed

didactic materials can be defined as any kind of resources and layouts that the

teacher creates, looks for or adapts to fulfill the daily needs in the

teaching-learning process. In the same line of thought, Tomlinson (1998, p. xi)

defines materials development as “Anything which is used by teachers or

learners to facilitate the learning of a language”. The interesting point

here is that the author comments that learning is a shared responsibility

between the teacher and the learners.

Due to the lack of

appropriate didactic resources for the ESP course I teach, materials

development is one of the main constructs that underpins this research.

Developing materials is an opportunity to find solutions for immediate teaching

problems at Escuela de Investigación Criminal and without depending on

foreign resources and help. Moreover, it is really refreshing when we teachers

not only instruct all the time, but also develop our own materials based on

reflection and concern, and look for new experiences as teacher-researchers. We

can produce solid and excellent material with the quality level of materials

created in English speaking countries.

From my point of

view, it is really exciting to explore this attractive possibility because it

helps the teacher reflect on his/her labor to continue seeking knowledge and

discovering new facets that enormously feed his/her intrinsic motivation. It is

also an opportunity to be updated with recent research in the educational field

(Núñez, Téllez, Castellanos, & Ramos, 2009). Reading

and being informed is an essential prerequisite to know about new theories and

practices that support the design of new materials.

De Mejía and

Fonseca (2006) argue that foreign materials are not always appropriate to any

context and do not fit in with the cultural and historical aspects of other

countries. Sometimes they integrate misunderstandings or fictitious concepts

about cultures in which the foreign language is taught. This is another

valuable reason to convince teachers to elaborate their own materials since

they belong to and are much closer to the culture and social situations in

which they are teaching.

Materials

development also requires attention to affective and motivational factors

(Núñez et al., 2009) since teachers should create an enjoyable

learning setting that fosters students’ confidence. When there is an

affectionate environment, learning is more motivating and effective because the

level of anxiety decreases and confidence increases.

However, materials

development is a tremendous responsibility that requires both preparation and,

above all, time. Searching for exercises, strategies, visual aids and contents

requires a lot of patience, time and creativity. These tools must be constantly

improved to optimize their effectiveness and replaced whenever they do not

fully meet the desired outcomes.

CALLA

CALLA is a helpful

resource to uphold academic and linguistic development. Also, it emphasizes

higher levels of thinking, fosters effectiveness, motivates learners and benefits

varied language level students towards learning a foreign language. I consider

this to be a model that works for content-based instruction and learning

strategies development, and therefore it was suitable for the development of

this research. Chamot, Barndhardt, Beard and Robbins (1999) state that CALLA

provides explicit instruction that assists students in learning both language

and content, and helps them to become more autonomous and better

self-evaluators of their learning process.

This approach is

based on the social-cognitive learning model that integrates the

students’ prior knowledge, collaborative learning and the development of

metacognitive awareness and self-reflection. It is an approach for learners of

second and foreign languages and uses explicit instruction in learning

strategies for academic tasks. The main purpose of this approach is to have

students both learn essential academic content and language, and become

independent and self-regulated learners through their increasing command over a

variety of strategies for the acquisition of knowledge. The main elements of

this instructional approach are summarized in Figure 2.

For this work, two

components of CALLA have been emphasized. The first one is the cognitive

learning model which defines learning as a dynamic process in which learners

are fully engaged and the information given is retained when it is important to

them. The second one has to do with the learning strategies defined as ways to

understand, remember and recall the information; these also have a close

relation with thoughts and actions that assist learning tasks and link the new

learning with the prior knowledge.

Instructional Design

In order to obtain

and organize evidence on the way students develop the reading comprehension

through the implementation of ESP content-based materials based on CALLA, I

designed reading workshops that focused on: (1) helping students to identify

vocabulary and expressions related to crimes, suspects and victims with the use

of their prior knowledge; (2) promoting the students’ interest in the

learning content and the English language; (3) training students in the use of

learning strategies for the development of different activities; (4) fostering

the students’ reading comprehension of short crime-related texts; (5)

aiding students in the recognition of vocabulary and expressions in context;

(6) creating and adapting activities to encourage students to use the learning

strategies as a routine to be more independent; (7) making the students aware

of the usefulness of English in their academic success, and (8) teaching

students to do an ongoing self-evaluation of their own learning process.

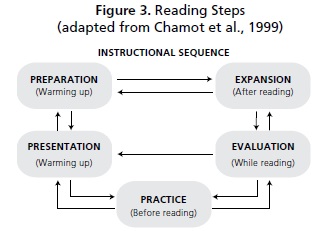

The reading

workshops were designed considering CALLA’s five steps (Chamot et al.,

1999) to organize the lesson plans flexibly so as to combine content, language

and learning strategies (see Figure 3).

Preparation (Warm

up): Students prepare for strategy instruction by

identifying their prior knowledge and the use of specific strategies.

Presentation (Warm

up): The teacher demonstrates the new learning strategy and

explains how and when to use it.

Practice (Before

Reading): Students practice using the strategy with regular

activities of moderate difficulty.

Evaluation (While

Reading): Students self-evaluate their use of the learning

strategy and how well the strategy is working for them.

Expansion (After

Reading): Students extend the usefulness of the learning

strategy by applying it to new situations or learning tasks.

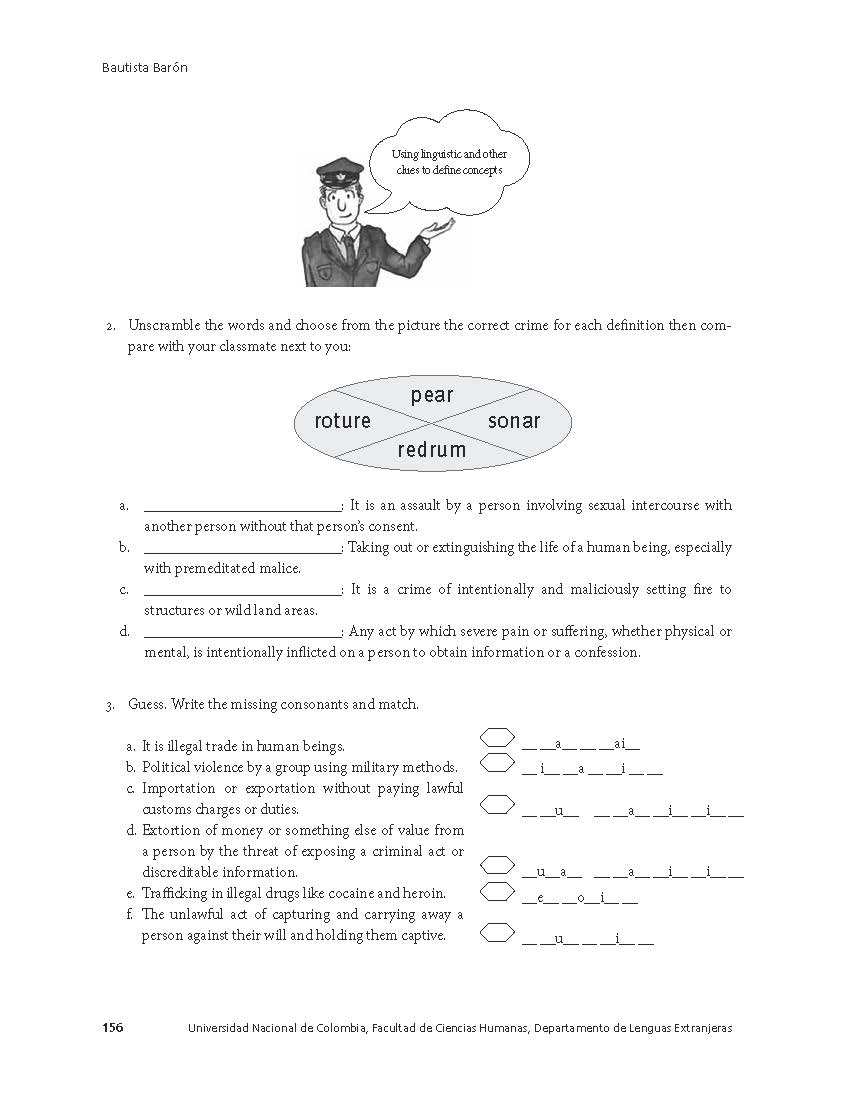

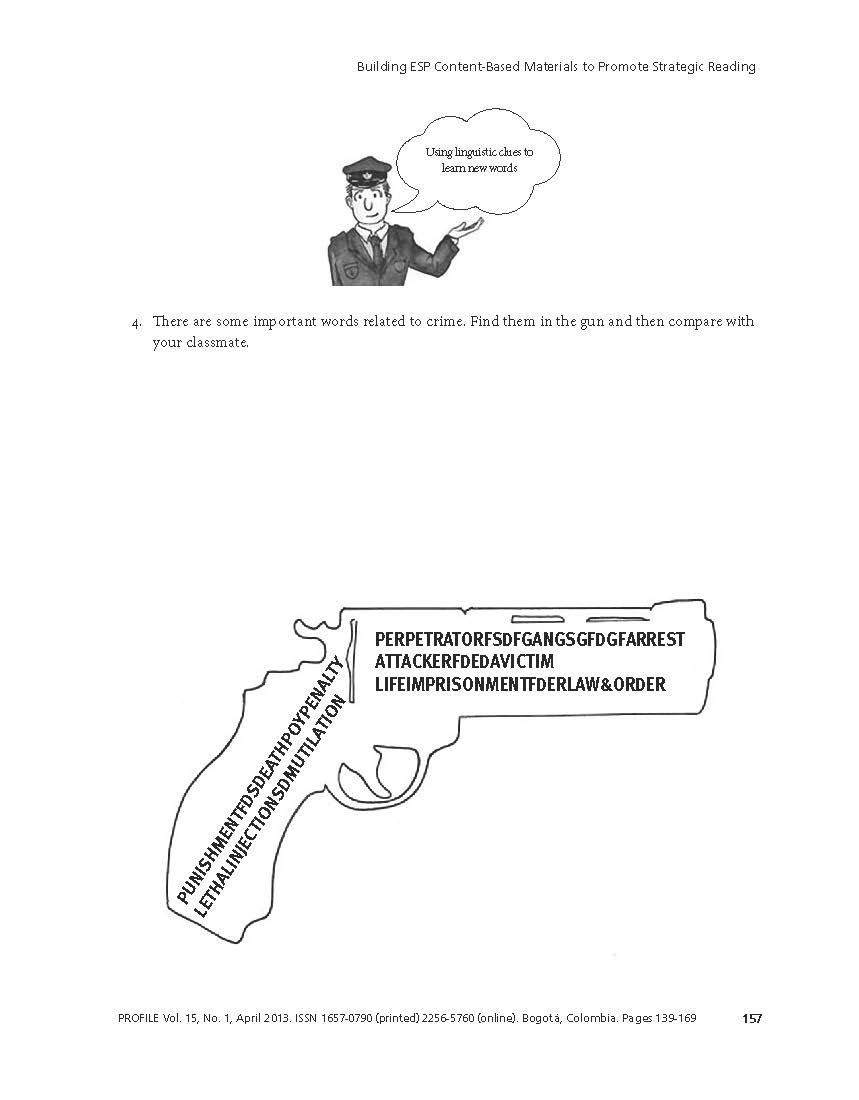

The workshops

integrated these steps which were implemented in three two-hour sessions. The

example presented in Appendix A refers to the first workshop where the teacher starts

by introducing the topic so that the students can define the concept of crime

(Warming up). Then, they identify crime vocabulary using pictures; they use

these new words in context through guessing, scrambling, matching, and

completion activities (Before reading). With this type of activities students

are prepared for the reading process and are also introduced to the recognition

of learning strategies. After that, they read short crime cases in groups

(While-reading) and the teacher revises the reading comprehension exercises

with the whole class (After-reading). Then, students reflect on their

experience of strategy use. In the last part of the workshop, there is a

self-evaluation that the teacher explains to students; in it, each student

reflects on learning attitudes, content learning, development of reading

comprehension skills and learning strategy awareness.

Research Design

The research

approach of this study is qualitative since it gives me the chance to have a

better understanding of my students’ behaviors, informing on their

thoughts, feelings, motivation, and performance. James, Kiewicz and Bucknam

(2008, p. 58) mention that “qualitative methods aid researchers in

extracting the depth and richness of the human experiences from their

subjects.”

This inquiry is an

action research whereby “the participants examine their own educational

practice systematically and carefully, using the techniques of research”

(Ferrance, 2000, p. 1). The purpose is to improve the way they address issues

and solve specific problems within the classroom; thus, I consider this type of

research to fit my study because it can generate genuine and sustained

improvements in language learning at Escuela de Investigación Criminal.

This action research comprised various phases: problem identification,

theoretical research, diagnostic stages, selection of learning strategies to be

promoted, development of reading materials and workshops data collection and

analysis.

Research

Questions

- How

does reading comprehension develop through the implementation of

content-based materials founded on the Cognitive Language Learning Approach

in an English course for undergraduate students majoring in Explosives?

- How can

students’ awareness of learning strategies be raised through reading

workshops using the Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach (CALLA)?

Context and Participants

The study was

conducted at Escuela de Investigación Criminal de la Policía, a

police training institute in Bogotá accredited by the Ministry of

National Defense. Regarding ESP, is imperative to improve the police

officers’ performance in English, because it has become an important

means of communication and information in their profession. Additionally,

during their studies, they have to work with different materials and situations

in English and use it to solve problems or to be informed. They also need to

manage technical vocabulary related to criminalistics to understand, for

example, foreign texts related to racketeering.

The group where the

research was carried out was attending the undergraduate program

“Technical Professional in Explosives.” It was composed of 16 male

students whose ages ranged from 24 to 36, and all of them participated in the

process. The English subject is divided into two levels: Basic English and ESP.

The students belonged to the latter, but their real language performance was elementary.

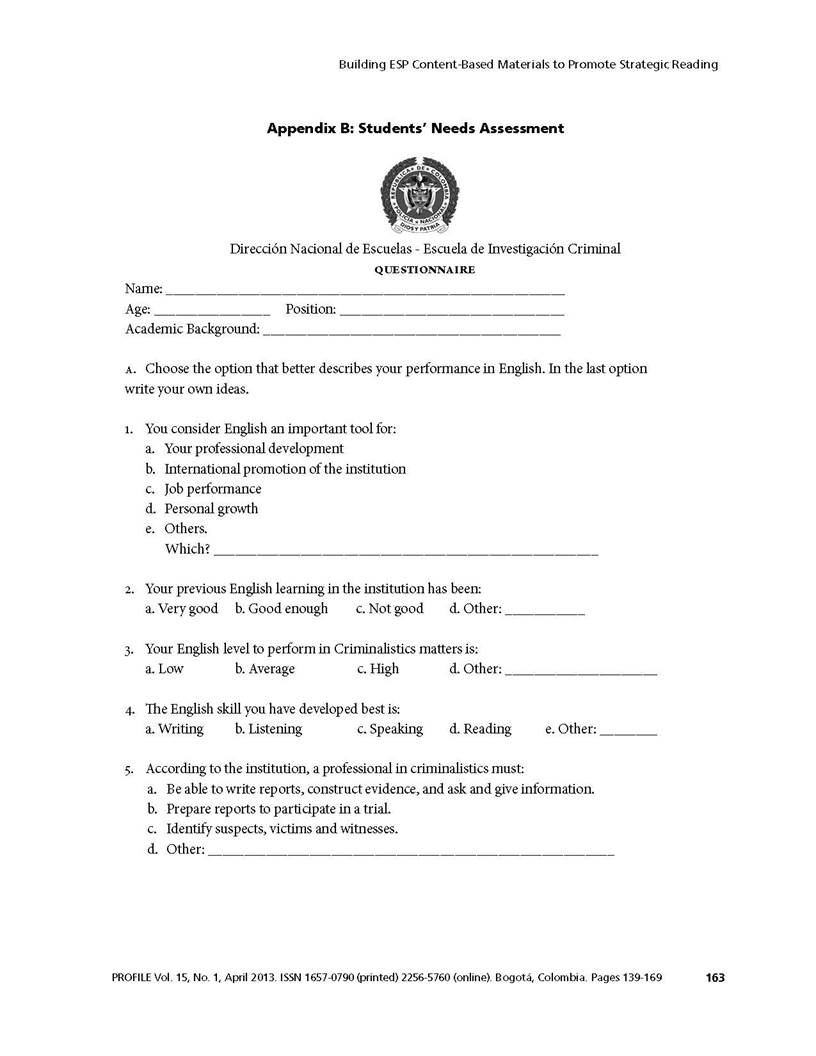

Data Sources

Freeman (1998)

considers the triangulation of data sources as a suitable methodological

strategy to test the credibility of qualitative analysis. Incorporating various

sources of information will make the research results more vigorous. First of

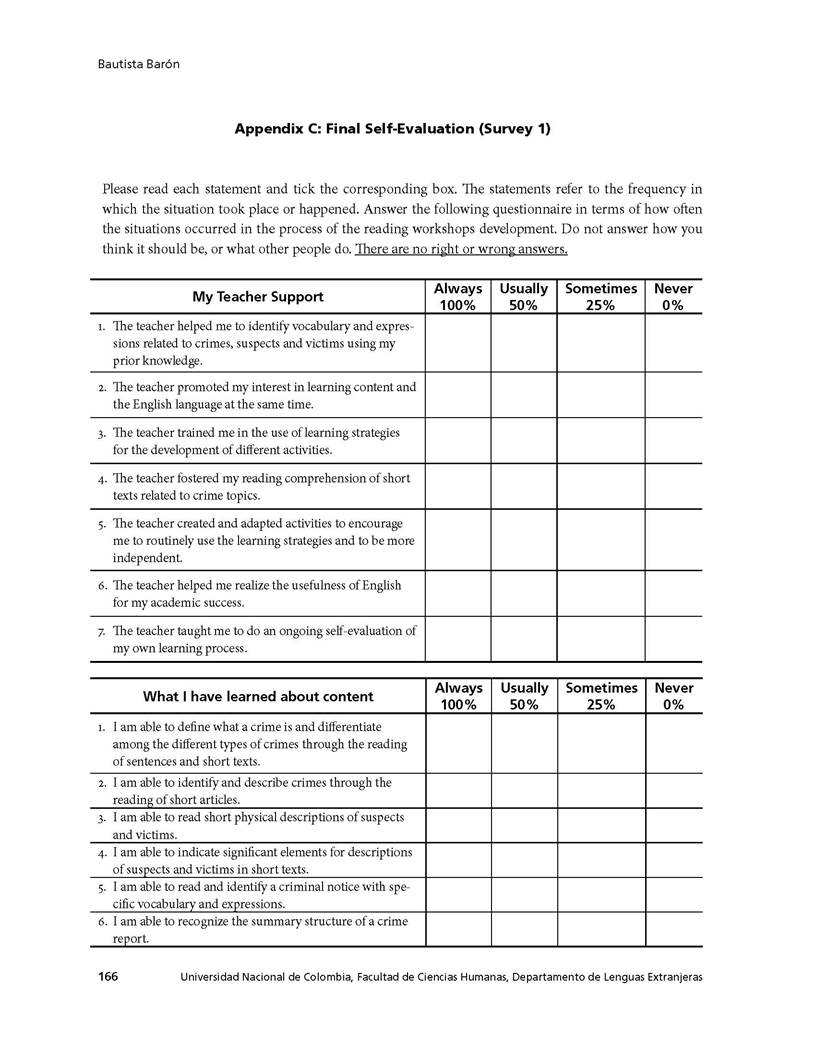

all, a needs assessment (see Appendix B) and a diagnostic

test were carried out for the diagnosis process and the design of the

workshops.

Three main data

sources were used during and after the implementation of the workshops:

students’ self-evaluation reports in six reading comprehension workshops,

and two surveys: The first survey (see Appendix C) was a final questionnaire to gather data about the students’

thoughts and behaviors, factual information and preferences; the second survey

(see Appendix D) consisted of three open-ended questions that the

students answered in their own words, providing qualitative information on

their learning process (Marsden & Wright, 2010).

Apart from these

sources, I also used three progress friendly reviews consisting of written

papers with different exercises to observe the students’ reading

comprehension progress through the implementation of the workshops. These

reviews were a very helpful tool since they provided evidence about the

students’ cognitive and metacognitive processes, and their ability to

choose the appropriate learning strategies to do the tasks. I also took

observation field notes and some photographs that document the development of

collaborative work in class and the teaching-learning environment in general.

Data Analysis

According to

Seliger and Shohamy (1989, p. 201), data analysis refers to “sifting,

organizing, summarizing and synthesizing the data so as to arrive at the

results and conclusions of the research”. The procedure was systematic

and included the description, the illustration of two research categories

supported with the information collected from various sources: Knowing the

what, the how and the what for and Building it up together. The type

of data analysis was the a priori approach since the categories were the

support of this study, as affirmed by Freeman (1998, p. 103): “It starts

with established categories and organizes them into a basic display, then names

by category and finds patterns in the display.”

Findings

The needs

assessment form was used before the intervention and included 14 multiple

choice questions to find out about the students’ previous English

learning experience and performance, their definition of strategy, their

opinions about reading comprehension in criminalistics, their learning activity

preferences and their meaning of autonomous work. The last question had to do

with expressing general comments and suggestions to facilitate the achievement

of the ESP objectives.

Most students

indicated that English was an essential component in their professional

development and they had to read a lot of material in English. Nine students

agreed that the type of learning materials that might help them in their

learning process could be guided reading workshops with a variety of

crime-science activities to allow some complete and holistic progress.

Finally, 8 students

mentioned that they felt more comfortable during collaborative work (between

the teacher and the students) and emphasized the importance of the

teacher’s help and guidance in the whole teaching-learning process. 6 of

them preferred to develop their work and class activities under the

teacher’s supervision and 2 felt better when working alone. A subsequent

diagnostic test, that included the reading of a crime text in which students

had to answer some comprehension questions, revealed that almost half of the

class (14 out of the 16 students did it) had a low level of language

proficiency (49%). I also asked them some oral questions after the test to know

how they solved each one of the exercises. I found that most of them were not

aware of the handling of strategies while doing the exercises.

Based on the

results of the students’ needs assessment and the diagnostic test, I

designed 6 reading workshops with activities that allowed them to work on

crime-science content and learning strategies for vocabulary and reading

development. To carry out the process of self-reflection, I selected and

adapted a brief evaluation at the end of each workshop to gauge the awareness

of their performance in terms of learning and autonomy. The two research

categories supported by the data sources are presented in Table

1 and explained below.

Knowing the What, the How and the What For

Suitable

Content and Linguistic Input

For the students it

was a double challenge since they had to handle both the language and the new

contents at the same time, which brings to my mind what Cantoni-Harvey (1987,

p. 201) says: “Language is essential for understanding content materials

and can be taught naturally within the context of a particular subject

matter.” Both the specific content (crimes, victims and suspects,

relevant suspect’s marks, criminal notice and summary of crime reports),

and the language (colors, parts of the body, clothes, simple sentences in

present and past tenses, expressions of time and places) were addressed by

means of a consistent application of an array of learning strategies that aimed

at developing the students’ reading processes.

The results of the

survey at the end of the course (see Appendix C) confirmed that 63% of the learners considered they were always able to

understand the contents developed through the reading workshops, and the other

37% could usually comprehend them.

In survey 2, the

students answered a question related to the contribution of the implementation

of the strategies in their content and language learning. Some of their answers

appear in the following excerpts (translated from Spanish):

Yes, the strategies help to understand the topics

Some strategies are easy to understand the crime words and expressions

The reading of the texts was easier with the help of the strategies Survey 2 (November 8th, 2010)

Students’

Learning Attitudes

In general, my

students’ attitude was really motivating as the planned topics had to do

with their own work as police officers. In fact they were willing to

participate, take risks without feeling disappointed, and accept more

responsibility for their learning from the beginning. Even though the

instruction of learning strategies was both interesting and useful to the

students, it was difficult for them to take full control of their own learning

process and this had a direct effect on their attitude depending on the tasks

and the time they had to invest in the workshops. Sixty-two percent of students

indicated that they always had positive feelings towards the class, the

learning process and their classmates. Ten percent answered they usually had

them, 5% sometimes and 23% did not give any answer.

Strategy Use

Awareness and Appropriateness

Students realized

they had used strategies and vocabulary but had not been aware of their use in

other contexts as can be verified in some of their opinions:

I didn’t know there were strategies to learn English

So, the strategies can be used for everything?

I learned vocabulary watching police films

Field notes (October 4th, 2010)

Some instruments

evidenced the fact that in the first tasks students tended to use direct

strategies like imagery, making associations, translating and placing new words

into a context, etc. They also began to realize which strategies were most

appropriate for each activity and that using them was helpful for developing

the tasks and doing the readings. The examples below confirm this variable:

It is imagery porque hay dibujos (It is imagery because there are drawings)

I need the strategy list para usarla cuando hago los exercises (I need the strategy list to use it when doing exercises)

Terrorism como in Spanish (Terrorism as in Spanish)

Field notes (October 4th, 11th, 2010)

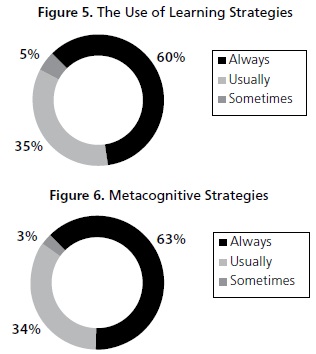

The information

from the survey at the end of the course showed that 60% of the students

considered they always implemented the learning strategies and used the reading

ones for a better understanding of texts and descriptions. Thirty-five percent

indicated that they usually implemented them and only 5% sometimes did so.

Collaborative

Work

The majority of the

students agreed that they felt more comfortable working with others and with

the teacher’s guidance. In this respect, the strategies that brought this

issue to the surface were the social ones: Asking for clarification or

verification and cooperating with peers, which are documented in the following

excerpts.

Teacher can I use the same strategies?

I like this exercise because we can work in pairs

I am always cooperating with my partners because they don’t understand

Field notes (October 12th, 2010)

The evidence

collected from the survey at the end of the course evidenced that 62% of the

students always respected others’ opinions and points of view and also

asked the teacher and classmates for help to solve problems and doubts. Ten

percent stated that they usually paid attention to their partners’ ideas

and only 5% sometimes did. Unfortunately, 23% did not answer.

What I enjoyed the most was the work in groups

I liked a lot to share ideas with my classmates

My partner was my best strategy because he clarified all my doubts

Survey 2 (November 8th, 2010)

The collaborative

work implied students working together as well as with the teacher, which

brought more resources into play, improving mutual trust, self-confidence and

support. Overall, this enhanced the human relationships that I, as a teacher,

deem an essential part of my mission.

For the

aforementioned reason, I included an item related to the teacher support in the

final self-evaluation to know if my role as a guide, facilitator and companion

was effective and supportive. The data gathered showed that 72% of the students

considered that I always promoted their interest in several aspects such as

learning content and language, instruction of strategies, development of their

reading comprehension of crime science related topics, and encouragement to become

independent readers able to use learning strategies as a routine. The remaining

27% asserted that I usually accomplished these goals and 1% declared I

sometimes carried them out.

Self-reflection

Self-reflection

implied the students’ awareness of the use of the learning strategies for

the development of reading comprehension. Ormrod (2004) defines this awareness

as “people’s knowledge of effective learning, and cognitive

processes and their use to enhance learning” (p. 358). It also has to do

with the form, the appropriate time and the reason to apply the learning

strategies that helped students to become autonomous and more self-regulated.

I took into account

the metacognitive model proposed by Chamot et al. (1999): organization of the

learning strategies which includes the reflection processes of planning,

monitoring, problem solving and evaluating, all useful for reading and

retention of language and content. The first step, planning, consisted

of socializing the objectives at the beginning of each reading workshop making

sure they are clear to all the students. Prior to starting the activities, I

invited them to look at the list of strategies and to select the ones they

considered more appropriate.

The second step, monitoring,

implied the students resorting to their prior knowledge, the previous workshops

or the dictionary to complete the tasks. The third step, problem-solving,

entailed having students use learning strategies like asking and verifying,

linking with already known materials, adjusting the messages, and using the

context, among others, to sort out problems during their implementation. The

last step, evaluation, comprised correcting and verifying the exercises

within their groups, which allowed them to reflect and become aware of their

results. This stage enabled students to reflect upon all these issues and

consider them to solve the following workshops and more complex tasks. The

evidence below exemplifies the students’ perceptions.

I need the list of strategies to do the exercise

I used placing new words into context because the words are in the first exercise

There are key words that help to recognize the type of crimes

To complete with letters I have to use the strategy asking for clarification and verification

Field notes (October 12th, 2010)

Building it up Together

Tailor-made

Materials

I took into

consideration an array of aspects to modify the syllabus and to create the plan

of activities for this ESP course. Among them, I incorporated students’

needs and expectations as the improvement of their reading comprehension, the

design and implementation of activities and tasks with an increasing degree of

complexity, the use of authentic materials as much as possible, and the

continuous teacher support and guide. This can be seen in Appendix A and in these students’ remarks:

In the way you learn more the difficulty is greater

Very positive experience because the methodology was innovative and easy

I think the learning was good thanks to the teacher’s methodology

I liked the readings because they were real

Survey 2 (November 8th, 2010)

Moving from

Simple to Complex Reading Comprehension Exercises

This aspect

features the reading process in the design, the implementation of the workshops

and the progress reviews. As getting information and its manipulation are two

of the main objectives in reading, I merged a variety of activities and tasks

to nurture mental processes, build knowledge, and improve learning skills to

strengthen the students’ reading comprehension abilities. I also

implemented permanent practical procedures to make it more effective.

Additionally, I chose appropriate teaching strategies to promote a didactic

reception of the reading passages moving from the simpler to the more complex.

In addition, I made

use of authentic readings that allowed students to read real information in the

foreign language, familiarize themselves with different reading processes and

become skilled in consciously recognizing the organization of the information

and the structure of the target language. In reference to this, Jacobson,

Degener and Purcell-Gates (2003, p. 13) propose that “It is best for

adult students to receive instruction which utilizes authentic, or real life,

materials and activities to be also grounded in the context of the

learner’s life outside of class.” Furthermore, the learners were

trained in the use of common expressions and vocabulary related to their field

of study which made them more engaged and enthusiastic. Here are some views that

illustrate this issue:

There are many words related to crime

I used placing new words into context because it helps me to know the meaning.

I used selecting and paraphrasing to understand better

The marks are very important to describe the suspect

Field notes (October 12th, 25th, 2010)

Figure

4 illustrates the process of developing materials that gradually moved from

the simplest reading exercises in the first workshops to the most intricate in

the last ones. In the first 4 workshops, according to the students’

perception of reading comprehension abilities, progress was increased 20%.

However, in workshops 5 and 6 almost 45% of the students did not complete the

survey, which made it impossible to check their complete insights. But

according to the graphic the students who did complete the survey (55%) kept

the perception of a possible improvement (40%).

Students’

Self-Appraisal of their Learning Attitude and Strategy Use Awareness

This last aspect

that supports the second category concerns the reflective manner in which

students reflect on their learning process and their attentiveness in the use

of strategies. According to Scott and Winograd (2001), when students are

strategic, “they consider options before choosing tactics to solve

problems and then they invest effort in using the strategy. These choices

embody self-regulated learning because they are the result of cognitive

analyses of alternative routes to problem-solving” (n. p.).

In the first

workshops I explained to the students every aspect to consider in the

reflection process and how to do it. However, it was not easy for them since

they were not used to doing it due to their cultural and educational

backgrounds. At the beginning they mentioned that their success or failure was

a direct result of the difficulty of the new concepts and vocabulary and lack

of personal abilities in the use of appropriate strategies. Fortunately,

through continuous practice they started to feel more comfortable judging by

how well they applied the strategies to do the tasks and then compared with

their classmates, discussed in group or talked with the teacher.

They also learned

that various strategies could be used in the same activity and began to think

about better ones they could have used. In general, there was a tendency to use

the most attractive to them, as imagery, asking for clarification and

verification, making associations, cooperating with peers and translating what

they found difficult to understand. However, when they started to gain control

over strategy use, they began to select more difficult strategies as placing

new words in context, taking risks widely, getting the idea quickly, adjusting

and approximating messages, using linguistic and other clues. The examples

below confirm the idea that students have specific preferences.

I always use imagery

I liked this exercise porque trabajamos de a dos (I liked this exercise because we work in pairs)

I liked this workshop porque hay mucha imagery (I liked this workshop because there is a lot of imagery)

I choose translating with the dictionary because hay muchas palabras que I don’t know (I choose translating with the dictionary because there are many words that I don’t know)

Field notes (October 12th, 25th, Nov 3rd 2010)

According to the

analysis of the final survey, 60% of the students recognized that the

self-evaluation at the end of each workshop was always important as part of

their learning experience and that they were able to choose the strategies by

themselves. Thirty-five percent said that they were usually able to do it, and

5% stated that only sometimes they knew how to do it. Similarly, 63% of the

students considered that they were always able to evaluate their own progress

in the new language; 34% were usually able and 3% only sometimes as shown in Figures 5 and 6.

Conclusions and Implications

Based on the data

collected, I concluded that the students understood the importance of ESP in

their professional performance, praising the creation of Criminalistics-based

reading workshops under pinned by CALLA principles. They improved their reading

comprehension by consciously selecting and applying learning strategies and

self-evaluating their own progress. In addition, there was a significant

advancement in self-sufficiency and communication in general as they were able,

at the end, to share their failures and achievements, identify their

difficulties, and look for possible solutions grounded on their own knowledge

while interacting with their classmates and the teacher.

They learned most

of the crime-science topics developed through the course mainly because those

had to do with their professional aim and interests. This fact helped them to

improve their language competence, have a very positive learning mood, be

willing to take risks and be more responsible during the learning process. The

use of a variety of direct and indirect strategies helped the students to

understand the content better even though in the first workshops they preferred

to use the direct ones since they were memory and cognition-related. Progress

was observed as they learned to use all the strategies and became aware of

their appropriateness in the different tasks.

To sum up, the

whole analysis gave me confidence to state that the development of reading

comprehension through content-based material was an effective process in which

the learners used their prior knowledge and built up on it as they fused their

experience as police officers with the language.

The field of

materials development not only gives teachers the opportunity to design new and

motivating activities for the students but also opens their minds to become

more proactive and creative in their teaching practice. Moreover, the use of

innovative materials encourages students to participate more actively,

increases general interaction, and gives an enhanced sense to the teaching

profession. It is also an alternative to the continuous use of the same

textbooks, traditional class activities and teacher-centered classes.

This issue is also

a good point to foster thinking about the current teaching practices and the

need for teacher-generated materials that cater to students’ language

learning and professional needs, likes and expectations. Indeed, contributing

to the betterment of the English level of our students through the development

of contextualized materials reduces the tendency of using traditional textbooks

and methods that are not always the most suitable for ESP context.

References

Alderson, J. C., & Bachman, F. L. (2000). Assessing reading.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cantoni-Harvey, G.

(1987). Content-area language instruction: Approaches and strategies. Reading,

MA: Addison-Wesley.

Chamot, A. U.,

Barndhardt, S., Beard, P., & Robbins, J. (1999). The

learning strategies handbook. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

De

Mejía, A. M., & Fonseca, L. (2006). Lineamientos para

políticas bilingües y multilingües nacionales en contextos

educativos lingüísticos mayoritarios en Colombia. Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá.

Ferrance, E.

(2000). Action research. Themes

in education. LAB at Brown

University: The Educational Alliance.

Freeman, D. (1998).

Doing teacher-research: From inquiry to understanding. A

Teacher Source book. San

Francisco, CA: Heinle & Heinle.

Grabe, W. (2004). Research on teaching reading. Annual Review of Applied

Linguistics, 24, 44-69.

Jacobson, E., Degener, S., & Purcell-Gates, V. (2003). Creating authentic materials and

activities for the adult literacy classroom. A

handbook for practitioners. NCSALL Teaching and training materials. Boston, MA: NCSALL

at world education.

James, E., Kiewicz, M., & Bucknam, A. (2008). Participatory action research

for educational leadership. Los Angeles, CA: Sage

Publications.

Marsden, P., &

Wright, J. (2010) (2nd ed.). Handbook of survey research. Bingley, UK: Emerald

Group Publishing.

Noles,

J. D., & Dole, J. A. (2004). Helping adolescent readers through explicit instruction. In T. L. Jetton, & J. A. Dole

(Eds.), Adolescent literacy research and practice, (pp. 162-182).

New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Núñez,

A. (2010). On the road 2. Elementary A. Bogotá, CO:

Uniempresarial.

Núñez,

A., Téllez, M., Castellanos, J., & Ramos, B. (2009). A practical material development guide for

pre-service, novice, and in-service teachers. Bogotá, CO: Universidad

Externado de Colombia.

Ormrod, J. E.

(2004). Human learning (4th ed.)

Upper Sadle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice-Hall.

Oxford, R. (1989). Strategy inventory for language learning (SILL).

Retrieved from http://homework.wtuc.edu.tw/sill.php

Oxford, R. (1990).

Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. New

York, NY: Newbury House.

Palinscar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of

comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities.

Cognition and Instruction, 1, 117-175.

Scott, G., & Winograd, P. (2001). The role of self-regulated learning in contextual teaching:

Principles and practices for teacher preparation. In A Commissioned Paper

for the U.S. Department of Education Project Preparing Teachers to Use

Contextual Teaching and Learning Strategies to Improve Student Success in and

Beyond School. Retrieved from http://www.ciera.org/library/archive/2001-04/0104parwin.htm

Seliger, H. W., & Shohamy, E. (1989). Second language research methods.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

The California Association of Criminalistics [CAC]. (2010). Code of ethics of the

California association of criminalists. Retrieved from http://www.cacnews.org/membership/CaliforniaAssociationofCriminalistsCodeofEthics2010.pdf

Tomlinson, B.

(1998). Introduction. In B.

Tomlinson (Ed.), Materials development in language teaching (pp. 1-24).

Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

About the Author

Myriam Judith

Bautista Barón studied

Philology and Languages (Spanish and English) at Universidad Nacional de

Colombia. She holds a specialization in Bilingual Education (Universidad

Antonio Nariño, Colombia), and a Master’s in Education with

emphasis on English Didactics (Universidad Externado de Colombia). She has

taught in different educational institutions in Colombia and Spain.

Acknowledgements

My infinite gratitude to my master and friend, Astrid

Núñez Pardo, for her patience and support. Special thanks to my graphic designers Nicolás

Ávila and Juan Fernández for their devotion and collaboration.

Appendix

B: Students’ Needs Assessment

Appendix

C: Final Self-Evaluation (Survey 1)

Appendix

D: Expressing my Personal Opinions (Survey 2)

References

Alderson, J. C., & Bachman, F. L. (2000). Assessing reading. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cantoni-Harvey, G. (1987). Content-area language instruction: Approaches and strategies. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Chamot, A. U., Barndhardt, S., Beard, P., & Robbins, J. (1999). The learning strategies handbook. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

De Mejía, A. M., & Fonseca, L. (2006). Lineamientos para políticas bilingües y multilingües nacionales en contextos educativos lingüísticos mayoritarios en Colombia. Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá.

Ferrance, E. (2000). Action research. Themes in education. LAB at Brown University: The Educational Alliance.

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher-research: From inquiry to understanding. A Teacher Source book. San Francisco, CA: Heinle & Heinle.

Grabe, W. (2004). Research on teaching reading. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 44-69.

Jacobson, E., Degener, S., & Purcell-Gates, V. (2003). Creating authentic materials and activities for the adult literacy classroom. A handbook for practitioners. NCSALL Teaching and training materials. Boston, MA: NCSALL at world education.

James, E., Kiewicz, M., & Bucknam, A. (2008). Participatory action research for educational leadership. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Marsden, P., & Wright, J. (2010) (2nd ed.). Handbook of survey research. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Noles, J. D., & Dole, J. A. (2004). Helping adolescent readers through explicit instruction. In T. L. Jetton, & J. A. Dole (Eds.), Adolescent literacy research and practice, (pp. 162-182). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Núñez, A. (2010). On the road 2. Elementary A. Bogotá, CO: Uniempresarial.

Núñez, A., Téllez, M., Castellanos, J., & Ramos, B. (2009). A practical material development guide for pre-service, novice, and in-service teachers. Bogotá, CO: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Ormrod, J. E. (2004). Human learning (4th ed.) Upper Sadle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice-Hall.

Oxford, R. (1989). Strategy inventory for language learning (SILL). Retrieved from http://homework.wtuc.edu.tw/sill.php

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. New York, NY: Newbury House.

Palinscar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1, 117-175.

Scott, G., & Winograd, P. (2001). The role of self-regulated learning in contextual teaching: Principles and practices for teacher preparation. In A Commissioned Paper for the U.S. Department of Education Project Preparing Teachers to Use Contextual Teaching and Learning Strategies to Improve Student Success in and Beyond School. Retrieved from http://www.ciera.org/library/archive/2001-04/0104parwin.htm

Seliger, H. W., & Shohamy, E. (1989). Second language research methods. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

The California Association of Criminalistics [CAC]. (2010). Code of ethics of the California association of criminalists. Retrieved from http://www.cacnews.org/membership/CaliforniaAssociationofCriminalistsCodeofEthics2010.pdf

Tomlinson, B. (1998). Introduction. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Materials development in language teaching (pp. 1-24). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Article abstract page views

Downloads

License

Copyright (c) 2013 Myriam Judith Bautista Barón

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You are authorized to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format as long as you give appropriate credit to the authors of the articles and to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development as original source of publication. The use of the material for commercial purposes is not allowed. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

Authors retain the intellectual property of their manuscripts with the following restriction: first publication is granted to Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.