The Practical Interpretation of the Categorical Imperative: A Defense

Palabras clave:

B. Herman, C. Korsgaard, I. Kant, O. O’Neill, categorical imperative. (es)

THE PRACTICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE CATEGORICAL IMPERATIVE: A DEFENSE*

Defensa de la interpretación práctica del imperativo categórico

CRISTIAN DIMITRIU

CONICET - Argentina

cdimitriu@hotmail.com

Artículo recibido: 05 de diciembre del 2011; aceptado: 13 de abril del 2012.

ABSTRACT

The article compares two different interpretations of Kant's categorical imperative −the practical and the logical one− and defends the practical one, arguing that it is superior because it rejects cases of free riding without necessarily rejecting cases of coordination or timing. The logical interpretation, on the other hand, leads to the undesirable outcome that it does not reject immoral cases of free riding, and to the desired outcome that it does not reject maxims of coordination/timing. Given that neither of them rejects maxims of coordination/timing (they are similar in that sense) and only the practical interpretation rejects free riding, the logical interpretation should be rejected.

Keywords: B. Herman, C. Korsgaard, I. Kant, O. O'Neill, categorical imperative.

RESUMEN

El artículo compara dos interpretaciones diferentes del imperativo categórico kantiano −la práctica y la lógica− y defiende la superioridad de la práctica debido a que rechaza los casos de free riding, sin rechazar necesariamente los casos de coordinación/tiempo. La interpretación lógica, en cambio, lleva al resultado indeseable de no rechazar casos inmorales de free riding, y al resultado deseable de rechazar las máximas de coordinación/tiempo. Dado que ninguna de las dos rechaza las máximas de coordinación/tiempo (y en este sentido son similares) y solamente la interpretación práctica rechaza los casos de free riding, debe rechazarse la interpretación lógica.

Palabras clave: B. Herman, C. Korsgaard, I. Kant, O. O'Neill, imperativo categórico.

Interpreters of Kant have not reached a consensus, even today, on how to understand the Categorical Imperative. In this article, I would like to focus on one specific source of disagreement on that issue: how free riding and coordination/timing cases relate to each of the main interpretations of the categorical imperative –the practical and the logical one. According to Herman (cf. 1993), the practical interpretation is weaker than the logical one, because it fails to distinguish cases of free riding from cases of coordination/timing. As a consequence of that, she claims, it ends up rejecting cases that are obviously not impermissibile. I shall argue in this paper that Herman's position is misleading, for it fails to acknowledge that a) the practical interpretation does not necessarily reject cases of coordination, as she suggests; and, more importantly, that b) the logical interpretation does not reject cases of real free riding –an undesirable outcome that the practical interpretation does not seem to have. In order to show this, I will argue that free riding cases, insofar as they could be considered instances of omissions, are different in nature from maxim/coordination cases.

Kant's first formulation of the categorical imperative is:

Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law. (Kant, cited in Kosgaard 66)

Interpreters1 have understood this quote as meaning that what can be willed is a problem of what can be willed without contradiction, after universalizing our maxims. This claim becomes clear when we read the following paragraph:

Some actions are of such a nature that their maxim cannot even be thought as a universal law of nature without contradiction, far from it being possible that one could will that it should be such. In others this internal impossibility is not found, though it is still impossible to will that their maxim should be raised to the universality of a law of nature, because such a will would contradict itself. We easily see that the former maxim conflicts with the stricter or narrower (imprescriptible) duty, the latter with broader (meritorious duty). (Kant, cited in Korsgaard 25)

According to Korsgaard (cf. 1985) (and, it seems, to the majority of Kant's interpreters), the first of these contradictions is usually called 'contradiction in conception', and the second 'contradiction in the will'. There are three possible senses in which there could be a contradiction in conception (i.e. a contradiction in the maxim itself): the Logical Contradiction Interpretation, the Practical Contradiction Interpretation, and the Teleological Contradiction Interpretation. In this paper I would like to focus on the first two.

On the Logical Contradiction Interpretation (LCI, from now on), a logical impossibility arises as a consequence of universalizing the maxim. In other words, the proposed universalized action would be unconceivable if universalized. The typical example of this kind of contradiction is the man who asks for a loan and (falsely) promises to repay it. To universalize the maxim of his action would lead to a world in which there would be no promises at all, because everybody would violate the practice of promising.

On the Practical Contradiction Interpretation, the maxim of an individual would be self defeated if universalized. In other words, the purpose of the individuals' action would conflict with itself. The same example as in the LCI could be considered, but under a different perspective. If somebody makes a false promise in order to obtain a loan, the contradiction would arise not from the fact that the universalized action (the practice of promising) would be unconceivable, but from the fact that the end of the person who makes false promises will be frustrated. As Kant says, the person "would make the promise itself and the end to be accomplished by it impossible" (66).

Korsgaard argues that the PCI deals with potential problems better than the other two. And it is precisely this claim that Barbara Herman wants to challenge. According to her, in "The Practice of Moral Judgment", Ch. 7, the LCI is stronger than the PCI. Although she admits that the logical interpretation also has some problems, she seems to suggest that these problems are not as serious as the problems that the practical interpretation has. What are, according to Herman, the problems of the practical interpretation? An issue that Korsgaard seems to have overlooked, she suggests, is that the practical interpretation fails to distinguish free riding from what she calls 'coordination' and 'timing'. In other words, her charge is that if it is correct that actions are impermissible when the universalization of a maxim conflicts with the purpose of the action, then we should consider impermissible not only cases of free riding, but also cases of coordination and timing. Herman offers two examples of coordination and timing to clarify what they are (cf. Herman 138):

1. A wants to save money by shopping in the after-Christmas sale. If everyone did this, then the after-Christmas sale would die (because the fact that there is an after-Christmas sale depends on the fact that most people buy things at a higher price before Christmas). If the after-Christmas dies, then the purpose of A would be frustrated, because he would not be able to buy presents which are for sale.

2. B wants to play tennis Sunday morning, when her neighbours are at church. At all other times the courts are crowded. If everybody acted as B does, the courts would be crowded at all times and the original purpose of playing tennis would be frustrated.

Case 1 is a case of coordination, and case 2 is a case of timing. In these two examples the agent takes advantage of the fact that others behave in ways that he or she is not behaving. Presents are cheap in the sale precisely because nobody buys them, and the tennis court is empty because everybody is at the church at that time. What Herman wants to show –if I understand her position correctly– is that these examples are not intuitively impermissible (it is far-fetched to think that A and B did something wrong), and yet they would be rejected by the practical interpretation. The reason is that in both cases the agents would frustrate their ends if the maxim of the action were universalized. In this sense, Herman says, coordination and timing would be no different from free riding: in both cases there would be an impermissible action involved. So Herman seems to have found two counterexamples that show that the practical interpretation rejects actions which should not be rejected. From this and for other reasons –which I will not analyze here– she seems to suggest that the logical interpretation of the categorical imperative is stronger than the practical one. In fact, if we analyze these two cases under the perspective of the logical interpretation, we would not find any contradiction at all. The logical interpretation, as defined above, prescribes that actions are impermissible when their universalization is unconceivable. It is clearly not the case, however, that a world in which everybody would be playing tennis or shopping in the after-Christmas sale is unconceivable. The most we can say about this, as Herman puts is, is that it is "foolish" or "pointless" (139).

I would like to argue that Herman's criticisms are misleading, and that the counterexamples that she gives against the practical interpretation are not effective enough to debunk it. First, let us recall that Herman claims that the practical interpretation fails to distinguish between free riding cases and coordination or timing cases. Her objection, in other words, is that the practical interpretation puts free riding cases and maxims of coordination in the same bag, so to speak, and rejects both cases for the same reason. The assumption seems to be that the practical interpretation could, in some sense, be equally applied to free riding cases and coordination cases, in a way that would render both inadmissible, after applying the Categorical Imperative procedure. Moreover, her assumption seems to be that the practical interpretation would have to either consider them both inadmissible or both acceptable actions, as it is if formulated.

It is, however, implausible to claim that coordination and free riding cases could be considered similar –in a way that the result of applying the Categorical Imperative to them would yield the same result– for they are cases which are different in nature.

In order to show in what sense omissions and coordination cases are different, let us consider the following examples:

1. A lazy factory worker decides not to do his job, because he knows that the rest of the workers will do it for him anyway.

2. A person overhears a guided tour in a museum, but did not pay for the tour.

What these two examples have in common, and in general all the cases of free riding, is that there is an omission involved. The lazy factory worker 'does not' do his job, even if he was expected to do so; and the person who overhears the tour in the museum 'does not' pay for it, even if he was expected to do so –if he wants to enjoy the benefits of the tour.

If we take a look at the examples considered earlier (the after-Christmas sale and the tennis court cases), we will hardly find an omission involved. On the contrary, the main feature in them is that the action involved is positive: to 'go' shopping, to 'play' tennis.

If this difference between cases of free riding and coordination is real (i.e. if there are in fact omissions involved in one case but not in the other); then, unlike the cases of coordination, the cases of free riding could be considered instances of omissions. And omissions, needless to say, are better understood as practical contradictions than logical contradictions. The reason why the practical interpretation would better handle them is that it does not seem unconceivable to universalize a negative action that ought to be done (the most that can be said about a case like that is that the we would have a sad world in which nobody acts according to what it is expected of them). Of course, omissions and free riding cases are impermissible because there is a previous duty –i.e. previous to the omission– that the agent has, and that the agent does not fulfill. This previous duty, as every duty, is derived from the maxims. What theses maxims are is highly mysterious to me; but, in any case, that is the topic of another paper. The upshot of all this is that Herman's claim that cases of coordination and free riding could be considered analogous or similar is misleading. The practical interpretation might possibly not resolve cases of coordination, but it would certainly solve cases of free riding.

On the other hand, it might be true that the logical interpretation does not reject cases of coordination, but it certainly does not reject real cases of free riding either (mainly because, as I said earlier, free riding cases are instances of omissions, which could be better handled by the practical interpretation). In fact, as Herman showed, the after-Christmas sale and the tennis court example would not be unconceivable if universalized (the most we could say about them is that they are foolish). However, we would find a similar result if we analyze a free riding case: it would not be unconceivable to universalize, say, example 1. The result would be just that workers do not do their job at all.

So the partial conclusion of all this seems to be that, overall, the practical interpretation is stronger than the logical one, because it considers impermissible cases of real free riding –which is what we are mainly interested in rejecting– whereas the logical interpretation does not seem to consider them invalid. That alone should suffice to give a stronger weight to the practical interpretation, because to find a procedure that would reject real free riding cases seems more relevant than to find a procedure that would not reject cases of coordination.

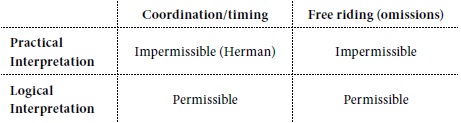

I hope all this becomes clear with the following table:

Under the logical interpretation coordination/timing cases are permissible, but free riding cases also are. Under the practical interpretation, free riding cases are impermissible and, according to Herman, coordination cases also are.

Although this would show that the practical interpretation is still stronger than the logical one, because an outcome in which real free riding cases get rejected is preferable over one in which free riding cases are considered permissible (regardless of how they deal with coordination examples); an issue that is worthwhile analyzing, anyway, is whether Herman is right in her claim that the practical interpretation would consider coordination/timing cases impermissible. If she is not, then the remaining suspicions about the practical interpretation would be dissipated.

There is, I believe, a possible alternative way to understand coordination/timing cases, which would show that Herman's readings of them is implausible. Claims such as "I want to be the president of France", "I want to be the national chess champion" or "I want to sit next to the exit door in an airplane, because it is safer" are all examples in which individuals want a special treatment for them. It would be impossible to achieve the ends that individuals claim to have, if everybody pursued them. And the cases that Herman offers as counterexamples to the practical contradiction interpretation (going to the after-Christmas sale or using the tennis court when everybody is at the church) do not seem to me substantially different from these cases. They could also be grouped as examples in which individuals want a special treatment for them. But is there anything wrong with wanting to be a chess champion or a president? Obviously not. If these cases were, in fact, counterexamples, then the upshot of this is that almost every case in which somebody wanted to do something which is impossible to universalize would be incorrect: to want a promotion in the working place, to book a room in a hotel, or even to eat bananas (assuming that there are not enough bananas in the world for everybody). Therefore, I believe that we should understand them in a rather different way (or else reject the whole idea of the Categorical Imperative as implausible). O'Neill (cf. 1989) has, in this sense, an interesting suggestion that could be relevant to discuss at this point. According to her, an agent's maxim in a given act cannot be equated simply with intentions. If, for example, somebody makes a cup of coffee for a new visitor, there would be many intentions involved in that action: the choice of the mug, the addition of the milk, the stirring, etc. But all these intentions would be secondary with respect to the underlying principle of the action: the maxim that guides our actions (in this case, maybe make the visitor welcome)2. There is, she says, a connection between the underlying maxim and the (set of) intentions that we have, insofar as it would be impossible to accomplish the end of our maxim if we do not preserve the mutual consistency of our intentions. So the intentions are, in a sense, "derived" or "secondary" with respect to the maxim that we have; but still necessary. Moreover, the ways in which the maxims can be enacted or realized can vary with respect to the situation or the context in which the individual is situated; and according to the culture in which he is. So, to continue with the coffee example, choosing the kind of coffee that the guest will drink could be the best way to make the visitor welcome in some cultures, but to make him choose the coffee could be the best way in others. In both cases the underlying maxim is the same (make him feel well) but the intentions through which we realize it are different (choosing his coffee and making him choose, respectively).

I think that; instead of considering coordination/timing cases as potential problems for one interpretation of the Categorical Imperative, or as cases which reinforce the interpretation of the other, we could simply understand them as intentions which are secondary with respect to a maxim. In order to elucidate what the relevant maxim is, and what the secondary intentions are, we should analyze the particular situation at hand. There is not anything that could be said a priori about them. So, for example, the case of the person who goes to the after-Christmas sale could simply be understood as an example of somebody who is acting on the maxim of taking advantage of the benefits of the market economy, and realizes that maxim by shopping in the after-Christmas sale that day only. There does not seem to be any inconsistency in enjoying the benefits of the economy. In fact, that is what everybody seems to do. It is important to note here the difference between the general maxim "enjoying the benefits of the market economy" and the particular intention of "shopping in the after-Christmas sale". If we differentiate one from the other, I think that there are reasonable grounds to understand that specific coordination case as universalizable. Something similar could be said about the case of the neighbour who uses the tennis court Sunday morning because everybody else is at church. That person could be simply acting on the maxim of preserving a good relationship with the neighbours (and therefore waits until nobody uses the court to use it) or on the maxim of maintaining a healthy body by following the doctor's advice of running only from 10 to 10:30. In any case, the fact that the person uses the tennis court at that particular moment to play is just an intention, ancillary to the underlying relevant maxim. This does not mean, of course, that any intention is valid as long as it realizes the maxim. The assumption here is simply that intentions and relevant maxims should be consistent with each other, and with the others' maxims and intentions. As O'Neill puts it,

The universality test discussed here is, above all, a test of the mutual consistency of (sets of) intentions and universalized intentions or principles. It operates by showing some sets of proposed intentions to be mutually inconsistent. It does not thereby generally single out action on any one set of specific intentions as morally required. (O'Neill 103)

Understood under this perspective, neither the case of the after Christmas sale nor the case of the person who uses the tennis court are clear cases of inconsistencies.

If the preceding analysis is correct, then Herman's cases are not really strong counterexamples to the practical interpretation, because there does not seem to be any good reason to think that the practical interpretation would have to reject cases like those. In fact, the after-Christmas sale and the tennis court case are not necessarily contradictory when universalized, so the unpleasant outcome that the practical interpretation inevitably leads to reject cases such as these does not seem to follow.

Going back to the comparison of the different interpretations and the problems that each of them have, I do not see any strong reason why, overall, the logical interpretation should be stronger than the practical one, as Herman suggests. Moreover, the practical interpretation not only does not seem to have the problems that Herman claims it has. but also seems to have important advantages over the conceptual one. In fact, it rejects cases of free riding (and, in general, any case in which an immoral omission is involved), but it does not necessarily reject cases of coordination or timing. The logical interpretation, on the other hand, leads to the undesirable outcome that it does not reject cases of free riding (i.e. immoral cases of free riding), and to the desired outcome that it does not reject maxims of coordination/timing. But the desired outcome of not rejecting maxims of coordination/timing is something that, as we saw, we also obtain through the practical interpretation; so, in that sense, they are not substantially different.

* Special thanks to Arthur Ripstein and Sergio Tenenbaum

1 For example Korsgaard, Herman, Wood et al.

2 O'Neill's argumentation becomes a bit confusing at this point, because in some parts of the text she suggests that what is fundamental is the underlying principle, while in others she suggests that what is fundamental is the relevant intention. In any case, her point is clear enough: what is most important is the relevant maxim that underlie our actions.

Bibliography

Herman, B. The Practice of Moral Judgement. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Korsgaard, C. "Kant's Formula of Universal Law", Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 66/1-2 (1985): 24-47.

O'Neill, O. "Consistency in action". Constructions of reason: exploration of Kant's Political Philosophy. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989. 81-105.

Referencias

Herman, B. The Practice of Moral Judgement. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Korsgaard, C. "Kant's Formula of Universal Law", Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 66/1-2 (1985): 24-47.

O'Neill, O. "Consistency in action". Constructions of reason: exploration of Kant's Political Philosophy. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989. 81-105.

Cómo citar

MODERN-LANGUAGE-ASSOCIATION

ACM

ACS

APA

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Visitas a la página del resumen del artículo

Descargas

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2016 Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución 4.0.

De acuerdo con la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-No Comercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Se autoriza copiar, redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato, siempre y cuando se conceda el crédito a los autores de los textos y a Ideas y Valores como fuente de publicación original. No se permite el uso comercial de copia o distribución de contenidos, así como tampoco la adaptación, derivación o transformación alguna de estos sin la autorización previa de los autores y de la dirección de Ideas y Valores. Para mayor información sobre los términos de esta licencia puede consultar: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode.

.jpg)